Welcome back. In the August 17 edition of this newsletter I outlined how the west got hooked on economic support. This week I explain how it got submerged under an ever-growing heap of red tape too.

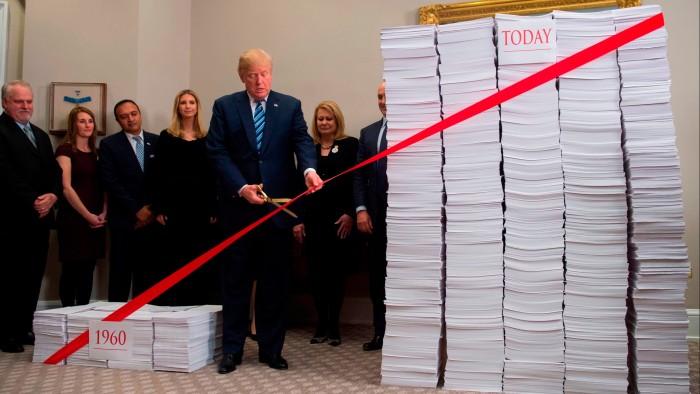

In the US, federal regulations now run beyond 190,000 pages, double their length in the late 1970s. According to official data, the annual government-wide paperwork burden on Americans is currently the equivalent of 11.7bn hours (that’s roughly 5.6mn people working full time for a year). It was 9.9bn a decade ago, according to American Action Forum.

The trend is similar in Europe. The total word count of EU legislation has increased by more than 700 per cent since the Maastricht treaty, based on data collated by Jonas Herby for the European Policy Information Center. The UK tax code is over 20,000 pages longer than it was in the mid-1970s.

Of course, many regulations exist to protect against various harms and enhance economic growth. For instance, food production standards support public health, transparency rules promote efficiency in markets, and banking regulations can reduce the risk of financial crises.

But they can also impede progress. For example, in Britain, planning applications often require piles of evidence to address potential negative impacts. Recent reasons for delaying or cancelling developments include the “moderate potential” to harm bats despite no evidence of the mammal’s presence, and a “snooker and pool needs assessment”, for a project that would demolish recreational facilities.

Across the rich world, there are also examples of excessive occupational licence requirements, overly prescriptive working hours restrictions, and complicated layers of local-level government rules.

Whether each new rule is well meaning or plainly obstructive, the cumulative burden still weighs on growth. Extra regulation, form-filling and checks slow decision-making and raise costs for businesses, households and government.

“Red tape acts as a tax on business investment, limits the entry of new competitors and encourages firms to divert efforts towards lobbying,” says Bruno Pellegrino, assistant professor at Columbia Business School, who has studied the impact of regulation on GDP.

“It restricts building and infrastructure development, and leads more resources to be allocated to bureaucratic activities in government. Altogether this leads to weaker growth and innovation, and poorer productivity across both the private and public sector,” he adds.

So why is red tape ratcheting higher? Here are three explanations:

First, as economies develop they become more complex. New industries, policy programmes and even crises generate demand for new rules, explains Patrick McLaughlin, research fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution.

“The global financial crisis triggered an expansion in prudential and conduct regulation. Digitisation has layered privacy, data governance, platform liability and now artificial intelligence compliance atop that,” he says. “The green transition is adding permitting, taxonomy, disclosure and technology-specific mandates.”

Divergent regulatory responses have also increased the burden of red tape on businesses with international operations.

In the past decade, trade restrictions have added insult to injury. “Subsidies, domestic-content rules and export controls have come with the turn towards protectionism and national industrial strategies,” says McLaughlin.

Indeed, US President Donald Trump’s tariffs — with their uncertainty, exemptions and complexity — are, in effect, a large new layer of red tape for business.

More broadly, crises and scandals can put pressure on governments to “do something”. That may involve rapidly enacting new rules, with less focus on long-term consequences or the impact of adding to the length of regulation.

Second, as societies age and grow richer the incentive to protect existing gains can raise demand for new regulations and block the rescission of old rules.

Indeed, Mancur Olson, an American political economist, observed that “distributional coalitions” tend to develop in stable societies, as power and wealth accumulates. These groups focus more on securing a larger share of existing output, rather than on creating new wealth.

In rich nations, aside from the aforementioned Nimbyism, these dynamics are reflected in pressure group activity and corporate lobbying.

For example, in the US, support from professional associations has contributed to an increase in occupational licensing, according to recent Cato Institute research.

Annual US lobbying expenditure has risen by $1.7bn in real terms since 1998. In the EU, the number of registered lobbyists has more than doubled since 2012.

Though many companies call for simplification, recent US research shows that larger firms, particularly in concentrated industries, tend to support more stringent regulations as a means to block competition. Lobbying for carve-outs more generally elongates the rulebook.

Pro-regulation appetite is mirrored in political platforms. Dr Lisa Zehnter, a researcher at the Manifesto Project, which analyses election manifestos in more than 60 countries, compiled mentions of pro-regulation statements in G7 political parties’ policy programmes. This sentiment — which includes positive references to consumer protections, protectionism and price controls — has trended higher since the early 2000s.

Pro-regulation sentiment today is close to levels that preceded the waves of deregulation ushered in by former US president Ronald Reagan and former UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s.

Third, regulations are hard to remove. Bureaucrats often adopt precaution to avoid facing political backlash or blame for things going wrong. This creates a bias towards over-regulation, and limits the repeal of old rules. The overall impact of a higher regulatory burden is, however, felt more diffusely.

“There is some evidence that voters do not reward deregulation as much as regulation,” says Columbia’s Pellegrino. “The burden of many regulations — for example those involved in running a business — is not salient to the majority of voters.”

Indeed, Austrian political economist Joseph Schumpeter argued that prosperity, over time, fosters social classes that are more detached from entrepreneurial activities, which can make them less beholden to free market interests.

Indicatively, a working paper by Bruegel shows that liberalising reforms have slowed globally since the 1990s. This is partly linked to rising public resistance. In advanced economies the intensity of reform efforts has declined over time, and a greater share of attempts are either dropped or diluted, according to the IMF’s October 2024 World Economic Outlook report.

The political obstacles to simplifying or cancelling previous laws can also lead to sub-optimal workarounds, including the creation of carve-outs and thresholds. This, in part, explains the growing length of the tax code across the rich world.

Complexity, in turn, makes it harder for bureaucrats to know how best to slash red tape.

Clearly, the drivers of the lengthening rulebook are complex and interlinked.

In recent years, there has been a swell in support for politicians with deregulation agendas. But not all red-tape slashing is good. The US’s so-called Department of Government Efficiency has led to indiscriminate cuts to important federal functions and funding.

Failing to adequately regulate new technologies and financial products or repealing rules put in place after long-gone crises pose risks too. Constant tinkering and deliberation don’t help either.

Rather than reactive and excessive regulation slashing, what’s needed is tighter policymaking in the first place, better knowledge in government of what particular regulations do, and regularised efforts to simplify rulebooks and take on special interests. Digitisation, improved data-sharing and AI can also reduce the paper load.

“Unless governments pair new initiatives with systematic pruning — including capping regulatory costs, sunsetting, and ex-post reviews of rules for efficacy — the result is steady accumulation of red tape,” says Hoover’s McLaughlin.

For economic growth, the challenge isn’t just about writing good regulations, it’s whether we can discipline the tendency towards their accumulation, too.

Send your thoughts to freelunch@ft.com or on X @tejparikh90.

Food for thought

Numerous studies show how financial bequests can influence the economic trajectory of the next generation. This paper explores another type of inheritance: our genetics.

Free Lunch on Sunday is edited by Harvey Nriapia

Source link