Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what Trump’s second term means for Washington, business and the world

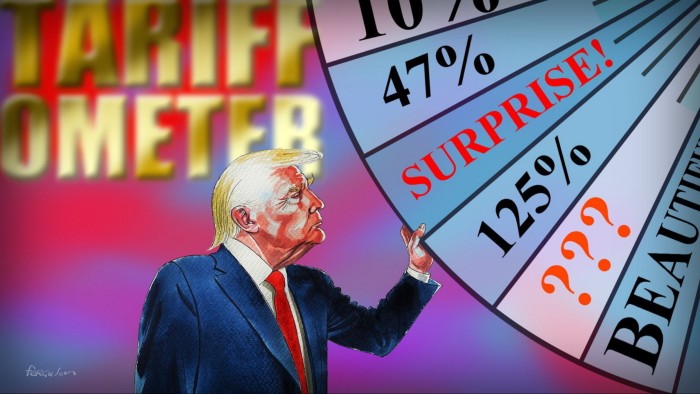

Over the past two decades, the world economy has staggered from one shock to another: the financial crisis; Donald Trump’s first-term trade war on China; the pandemic; post-pandemic inflation; Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; the war in the Middle East; and now Trump II’s “let’s-blow-the-world-economy-up-for-fun” trade war, which has brought average US tariffs back to levels not seen for over a century, with possibly more to come if “reciprocal tariffs” are reimposed. (See charts.)

It is the job of the IMF to make sense of what this unnecessary shock might mean for the world economy. In its latest World Economic Outlook, it does its very best to do so. This does not mean it knows. Nobody does. Beyond the fragilities bequeathed by previous turmoil and the usual ignorance of how our complex global economy operates, we all face the huge difficulty that we have no idea what Trump will do next or, for that matter, how others will act in reply.

As a result, the biggest reality we can identify, apart from the prohibitive tariffs imposed by the US and China on each other, is the elevated uncertainty. This is itself economically paralysing. Indeed, one of the many depressing realities of the Trump administration is its failure to understand that, in a free society, arguably the most important role of government is to reduce uncertainty, not do whatever it can to raise it.

Consider the backdrop to the Trump shock. As Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, the fund’s economic counsellor, notes in his foreword to the WEO: “The global economy showed surprising resilience during the severe shocks of the past four years.” Inflation has fallen from prolonged highs. Unemployment and vacancy rates have also headed back to pre-pandemic levels. Global growth returned to around 3 per cent, lower than in the past, but at least respectable, while output approached potential. Yet many economies also stayed below pre-pandemic trends. The US was the biggest exception on the upside.

Things then were getting better but there were also significant fragilities. In many countries, inflation is not yet securely back to target. Public debt levels and deficits are generally at high levels, largely as a result of efforts to cushion earlier shocks. Interest rates are also at elevated levels. Thus, it is far harder to use fiscal or monetary policy to cushion blows today. No wonder growth forecasts are being downgraded. No wonder, too, Trump is waging war on Jay Powell at the Federal Reserve. The latter is right to resist. I remember how devastating the inflation cycles of the 1970s were to confidence. We need no repeats in our fragile world economy.

The IMF also explains how steep tariffs operate as a supply shock on those imposing them, which lowers productivity and increases unit costs. Those that are hit face a negative demand shock as export demand diminishes, putting downward pressure on prices. As the WEO says: “In both cases, trade uncertainty adds a layer of demand shock as businesses and households respond by postponing investment and spending, and this effect may be amplified by tighter financial conditions and increased exchange rate volatility.”

The WEO’s “reference forecast” is based on measures announced as of April 4. It states “global growth is projected to fall under this option from an estimated 3.3 per cent in 2024 to 2.8 per cent in 2025, before recovering to 3 per cent in 2026. This is lower than the projections in the January 2025 WEO Update, by 0.5 percentage points for 2025 and 0.3 percentage points for 2026, with downward revisions for nearly all countries.”

This forecast omits the impact of changes since April 4. On April 9, for example, Trump placed a 90-day pause on the higher tariff rates on many countries. At the same time, tariffs on Chinese goods were increased while the 10 per cent minimum on all countries remained. China countered again. Two days later, the US said it would exempt many electronic devices. China raised tariffs on US goods once more on April 12. Then as of April 14 — the cut-off date for the WEO, the report states — “the US effective tariff rate on Chinese goods was 115 per cent, while that imposed by China on US goods was 146 per cent, and the US overall effective tariff rate on the world stood at about 25 per cent, up from under 3 per cent in January 2025.”

This, in brief, is a world economy facing huge downside risks: brutal decoupling of the superpowers; pressure from both the US and China to choose between them; severe loss of confidence in US trustworthiness and good sense and so flight from the dollar; fiscal and financial crises; financial and economic disruption in emerging and developing countries in a world with rapidly shrinking official assistance; profound economic and humanitarian crises; exacerbated social and political instability; and even major wars.

Naturally, the fund cannot explore the geopolitical implications of the possible dismembering of the integrated world that the US itself created over the past eight decades. But the question is whether the full extent of these downside risks can be avoided. It points to the possibility that the fear of the moment will lead people to step back from the brink and so fashion a new world order. It is possible, for example, that China will at last realise that it cannot rely on global demand to pull its huge economy. If it at last shifts to a domestic demand-led economy, it can at least mitigate the global crisis. It is possible, too, that the US will abandon its futile nostalgia for a manufacturing economy that will never return and so shift towards more measured — indeed, saner — trade policies.

I am not optimistic. But I can hope. We cannot afford to remain on a path towards economic and political disaster.