Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

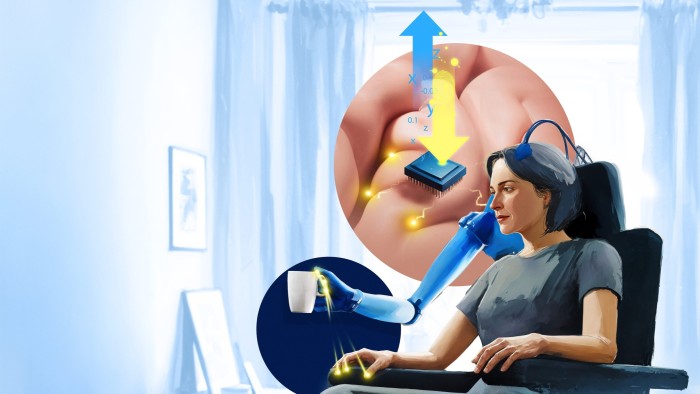

Scientists have for the first time given a realistic sense of touch to people operating a robotic hand via signals sent from their brain, marking the latest advance in neurotechnology research to help overcome disabilities.

The University of Chicago study, published in Science on Thursday, worked over several years with volunteers paralysed by spinal cord injuries. They had tiny electrodes implanted in the brain’s sensory and motor regions that control sensations and movements in the arm and hand.

The subjects learned not only to grasp objects by driving a bionic limb with their thoughts — a feat achieved in previous research — but also to feel edges, shapes and movements. Such rich two-way communication between the robotic hand and brain raises hopes that intuitive systems could improve the lives of millions of disabled people.

“The research went beyond anything that has been done before in the field of brain-computer interfaces,” said Giacomo Valle, who led the Chicago study and recently moved to Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden.

“We are at another level of artificial touch now. We think this richness is crucial for achieving the dexterity, manipulation and tactile experience typical of the human hand.”

The researchers mapped the brain areas that respond to touch in specific parts of the hand and fingers, using implants made by Blackrock Neurotech, the longest established US manufacturer of BCIs.

“Electrodes next to each other in the brain don’t create sensations that ‘tile’ the hand in neat little patches with one-to-one correspondence,” said Chicago’s Charles Greenspon, a senior author of the study. “Instead the sensory locations overlap.”

The researchers developed programs that used the overlapping of touch zones to enable participants to experience the sensation of something moving smoothly over their bionic fingers, such as a steering wheel in a driving simulator. They could also identify letters of the alphabet traced on their fingers.

Greenspon said more progress in restoring a lifelike sense of touch to people living with amputation or paralysis depended more on increasing the sensitivity of synthetic skin on prosthetic hands than developing better brain implants.

Scientists also needed to improve subjects’ “proprioception” — the sense of knowing where bionic limbs are positioned.

The research was funded by the US National Institutes of Health through the Cortical Bionics Research Group, a university consortium. Valle said his move to Chalmers had extended its activities to Europe, where there has been less investment in neurotechnology than in the US.

A similar approach could help people with other types of sensory loss, the scientists said. For example, they are working with surgeons and obstetricians at Chicago university on a Bionic Breast Project, which aims to produce an implantable device to restore the sense of touch that is missing after mastectomy.

Commenting on the findings, Paul Marasco, a neuroscientist at Cleveland Clinic in Ohio who was not involved in the research, said: “The beauty of the study . . . is that they are discovering how brain circuits are processing tactile information at a very local level.

“They are at the first stage of learning to speak the brain’s language, which no one really understands.”

Source link