Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Artificial intelligence myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

The writer is a novelist

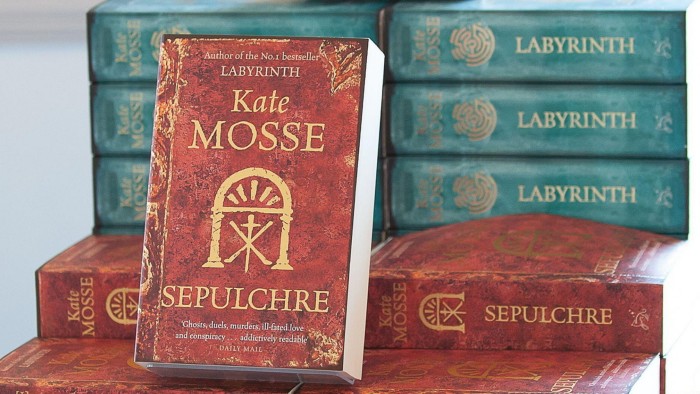

In 1989, we bought a tiny house in the shadow of the medieval city walls of Carcassonne. It was the beginning of my love affair with Languedoc — the history, the arcane mysteries hidden in the landscape, the endless blue sky, the light over the mountains at dusk. It would inspire my first historical adventure novel, Labyrinth, which would go on to be translated into 38 languages and sold in more than 40 countries. Its global success is the reason I could give up my day job and become a full-time writer.

Imagine my dismay, therefore, to discover that those 15 years of dreaming, researching, planning, writing, rewriting, editing, visiting libraries and archives, translating Occitan texts, hunting down original 13th-century documents, becoming an expert in Catharism, apparently counts for nothing. Labyrinth is just one of several of my novels that have been scraped by Meta’s large language model. This has been done without my consent, without remuneration, without even notification. This is theft.

I’m excited by artificial intelligence and its possibilities. Using technology to enhance, develop, experiment and innovate is part of any artist’s toolkit. We need time to create and, potentially, AI can give us breathing space to do the things we love. But stealing intellectual property is an assault on creativity and copyright, and will undermine the UK’s world-leading creative economy. The time has come to group together and act.

This has been a busy month in parliament for AI. On December 3, the Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society launched the report “A Brave New World?” at a meeting of the All-Party Parliamentary Writers Group. This survey of some 13,500 authors’ attitudes to AI threw a hand-grenade into the one-sided debate about the illegal scraping and crawling of authors’ work and the misconceptions surrounding it.

On December 9, Baroness Beeban Kidron convened creators to discuss three proposed amendments to the data (use and access) bill currently going through parliament, which would make UK copyright law enforceable in the age of generative AI.

This occurred ahead of the government’s consultation about how to boost trust between sectors, ensuring AI developers provide rights holders with greater clarity about how their material is being used. So far, so good. Except, when the framework of the consultation was revealed, it became clear that it was an attempt to fatally weaken the UK’s copyright laws in the name of “progress” by suggesting creators and rights holders should have to “opt out” of their work being used for AI training.

When the House of Lords debated the Kidron amendments this week, peers were united in their scorn for the government’s plans, with Kidron observing: “The government have sold the creative industries down the river.”

AI companies present creators as being against change. We are not. Every artist I know is already engaging with AI in one way or another. But a distinction needs to be made between AI that can be used in brilliant ways — for example, medical diagnosis — and the foundations of AI models, where companies are essentially stealing creatives’ work for their own profit. We should not forget that the AI companies rely on creators to build their models. Without strong copyright law that ensures creators can earn a living, AI companies will lack the high-quality material that is essential for their future growth.

The UK has one of the most thriving, innovative and profitable creative industries in the world, worth some £108bn per annum. The publishing industry alone contributes £11bn each year and has the potential to grow another £5.6bn in the next decade. It supports 84,000 jobs and leads the world in publishing exports, with 20 per cent growth predicted by 2033. In the film industry, 70 per cent of the top-20 grossing films in 2023 were based on books.

One of the reasons for this global success is because we have robust and fair copyright laws. The UK pioneered these. The Statute of Anne, passed in 1710, aimed to encourage learning and support the book trade, to create a framework where writers who originated work retained full rights, making it illegal for publishers to reproduce work without permission or payment.

It is this robust and fair system that the government will undermine if it pursues an opt-out — or “rights reservation” in the new parlance — rather than an opt-in model. Why should we writers shoulder the burden of preventing AI companies from stealing our work? If a producer wants to make a film of it, or a radio show, or a piece of theatre, they approach us and we do a deal. Though the technology is new and developing, the principle is the same. AI is no different. It is not just a matter of fairness, or of acting illegally, but of economic growth. If creatives have to spend time trying to track down AI companies to stop our work being scraped, we will have less time to work. This will, in turn, diminish our world-beating creative industries and damage growth.

I wholly support the government in its determination to harness the future and be a world leader in AI innovation. Sixty-plus years ago, at the Labour party conference in 1963, Harold Wilson talked about the “white heat of technological revolution” and a “university of the air”. This Labour government is following in those forward-thinking footsteps. But weakening copyright is not the way to do it. Putting the burden on authors and other creators to opt out is not the way to do it. Without original work, there is nothing.

Source link