It is late in the year and even though many central banks are meeting this week, it is time to look back at 2024 and learn lessons. Inflation has fallen and central bank forecasts have improved, but it has not all been smooth sailing.

The victory over inflation is not complete, the public remain angry, financial markets have had a terrible year predicting central bank moves and economic circumstances are far from wonderful in advanced economies. Here are five lessons for 2025.

1. We are getting close to declaring victory over inflation

Inflation is very close to the standard 2 per cent target in the vast majority of advanced economies. The largest deviation from the headline inflation target rate in the US, Eurozone, UK and Japan is 0.3 percentage points, as shown in the chart below. The divergence is a little larger in some of these economies when measured at annualised rates of more recent months (click on the chart to view), but there are no definitive signs of inflation trends moving far away from target levels.

Much better than eyeballing the chart is to take a statistical approach to assess underlying inflation. The pink line shows a meta technique my colleagues and I have devised at the FT, with all the difficult stats undertaken by Joel Suss.

What we call “FT core inflation” is the outcome of a regression model of numerous other underlying measures to find the best predictor of long-term trends, measured by the three-year moving average headline inflation rate. The methodology and some robustness checks are here.

FT core inflation shows the UK and the US still have some way to go to eradicate inflation from their economies, although progress in the UK is ongoing. The US will also resume its path to the inflation target if it can avoid a difficult start to 2025, unlike the rocky few months of price rises in early 2024.

2. The last mile of inflation control is difficult to define

There has been much talk of the last mile of inflation control over the past year, whether by me, thinking it was easy, or by officials outlining their concerns. I was struck last week by this post on X by Professor Jason Furman of Harvard university, noting that the latest US three-month annualised CPI inflation excluding energy and food was higher than 98 per cent of the data points in the inflation control era between 1992 and 2019.

“You can make excuses about noisy factors. But there were a lot of three-month periods during those decades with noisy factors too,” he said, implying that the Federal Reserve was struggling with the last mile in the US.

Furman’s idea was so sharp, I decided to extend his analysis to other inflation measures and time periods to see whether it was an odd result or told us something more profound.

The chart below for the US shows the latest headline inflation excluding energy and food and the FT core measure over different time periods compared with every reading between 1992 and 2019.

These results are not as worrying for the Fed as the single estimate Furman produced. US headline inflation is within the 1992 to 2019 inter-quartile range (the box part of the box plot) on all measures and also on the FT core measure on the three- and six-month annualised basis. It is only outside that on the 12-month basis, reflecting big monthly price rises in the first quarter of 2024.

The standard “core” measure, excluding energy and food, is the exception here on both PCE and especially CPI inflation, suggesting it does contain unusual biases. So, my tentative conclusion is that the three-month core CPI being at the 98th percentile is an exaggeration of the underlying US inflationary problem.

In Europe, many more of the latest data points are well outside normal ranges and some measures — for example the core 12-month inflation rate — are higher than any point of the pre-Covid period 1996 to 2019.

Should we worry? No.

First, headline inflation is in normal ranges and close to or below 2 per cent. Second, the latest trends in Eurozone inflation are weaker than earlier in the year. Third, and most importantly, the Eurozone had too low inflation for most of the 1996 to 2019 period and the FT core rates (remember, this is the best predictor of underlying inflationary trends) are hovering around 2.3 per cent. That is very close to target.

If we want to get an even more extreme comparison of current inflation rates than the historical average, take a look at Japan, below. The average rate in the first 19 years of this century (the different time periods relate to the ease of extracting the data) was roughly zero and the Bank of Japan wants to break out of a zero inflation world.

Its last mile, therefore, is to bring inflation somewhere close to 2 per cent, which will inevitably be an outlier compared with the past. The good news for officials in Tokyo is that nearly all the latest data, especially the FT core measure, suggests it is succeeding in its ambitions. Thirty years too late, perhaps, but better late than never.

The UK has the most challenging circumstances when it comes to this last mile analysis. Most of the latest data is outside the inter-quartile range of the 1992 to 2019 period, although there are signs of progress, especially with more recent data.

There is no doubt that UK inflation still needs to fall, so the Bank of England’s “gradual” approach to rate cutting is wise. If recent good readings on the FT core measure are a good guide, then the bank will receive the reassurance it needs sometime in the spring.

3. Forecasts have been better, but that is not all good news

If there was one thing that undermined confidence in central banks over the past few years it was their inability to anticipate a persistent rise in prices. That is now over.

The Fed’s US core inflation forecast might well get revised a little higher on Wednesday, but with the data almost in, it will not have to worry about the accuracy of these inflation forecasts.

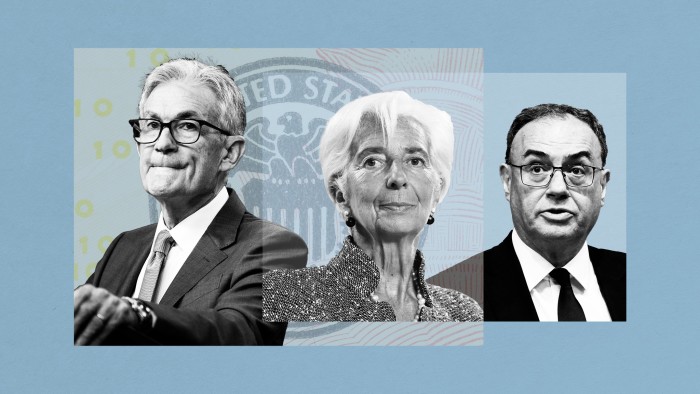

The ECB’s record is, if anything, even stronger. Core inflation has been slightly higher than it predicted earlier this year, but it was out by only a few tenths of a percentage point, as president Christine Lagarde highlighted on Monday.

It is not all good news for the ECB, however. Compared with December 2023, its latest forecasts had weaker growth in 2024, 2025 and 2026, with lower interest rates and slightly less inflation. Without saying so, the ECB has downgraded its view of the underlying growth rate of the Eurozone economy significantly over the past year.

In the UK, Andrew Bailey likes to say that inflation is running 1.5 percentage points below the November 2023 forecast. It is. But that tells you more about the November 2023 forecast being an outlier and baking in too much residual inflation than anything else. To be specific, it tells you everything about the BoE’s energy price assumptions in November 2023 and little about the bank’s success in inflation control.

The chart below shows that subsequent forecasts and inflation have proved to be much more in line and the BoE is now expecting headline inflation to rise higher in 2025 than previously. It will hope it is wrong on that count.

The Bank of Japan forecasts annual average rates of inflation, undermining efforts to gauge its success, but there is nothing in the latest data that suggests it is struggling to understand its economic trends.

4. Central banks bear some responsibility for financial market failures to forecast interest rates

If central banks have had a pretty decent year in controlling inflation and forecasting economic trends, financial markets have had a shocker.

In the most deep and liquid market for forward interest rates, US investors have swung wildly between expecting seven quarter-point interest rate cuts in 2024 in January, fewer than two in April, six in September and now four in December. Similar sentiment has flowed across the Atlantic to the ECB and BoE forward interest rate markets. This is not an environment of stable financial conditions.

Why have financial markets been such a poor guide, especially in the US? Most likely because they have been super data dependent, getting spooked by poor inflation data at the start of the year and then a few weak labour market readings in the summer. Blame should not rest entirely with investors, however. They were reacting to their understanding of the Fed’s reaction function, which has appeared jumpy in response to monthly data points all year.

By the way, if you think the predictive failure of financial markets in 2024 should make you follow academic economists instead, you would also be wrong. Only 16 per cent of those surveyed by the Clark Kent Center at University of Chicago thought there would be four interest rate cuts or more in 2024 at this point last year.

5. Oh, and people hate inflation

Academic surveys have shown that the public have a poor understanding of inflation and really dislike periods of price rises. Electoral confirmation of these findings came in waves during 2024, with governing parties taking a pounding around the world.

The chart below from my colleague John Burn-Murdoch says it all.

What I’ve been reading and watching

-

In what must be the least surprising development of 2024, President-elect Donald Trump now says reducing prices will be “very hard”, having campaigned on the promise of bringing them way down

-

Martin Sandbu argues for the ECB to take more note of its secondary mandate to support the EU’s economy loosely and lower the price of investing in certain areas such as the green transition. The alternative view is that governments can do that sort of taxing and subsidising, but Martin makes the best case possible

-

In a divergent American continent, Brazil raised interest rates by another 1 percentage point last week to 12.25 per cent, while Canada cut its by half a percentage point to 3.25 per cent

-

Ruchir Sharma says it is time to bet against US assets

Source link