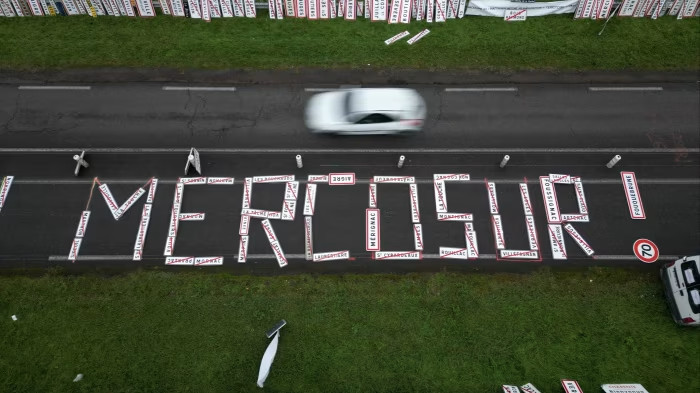

At last a Trade Secrets that isn’t about Donald Trump and in fact doesn’t mention him at all, except for the sentence you’ve just read. The European Commission and ministers from the Mercosur countries on Friday agreed a revision of the deal they previously signed in 2019. (It’s been a long road: talks started in 1999, so long ago that EU and Mercosur member countries Argentina and Germany were then led respectively by Carlos Menem and Gerhard Schroeder and both men had yet to be discredited.) As usual we await the full text, and of course it will take months of legal scrubbing and translation before it even gets to the tough ratification battle that awaits it in the EU. It’s really not a done deal. But still, arriving at this point is a big achievement. Today’s newsletter contains various thoughts on the matter. Charted Waters is on posh whisky. Question for readers this week: will this version of the deal get ratified by, say, June 2026? Email me at: alan.beattie@ft.com.

Get in touch. Email me at alan.beattie@ft.com

The art of the deal

It’s real Jurassic Park stuff. The European Mercosaurus was considered endangered by most and extinct by some, but it’s roared back to life.

Or for a more up-to-date temporal metaphor, it’s as if a news story has dropped through a wormhole from ten or twenty years ago. An across-the-board deal between big trading partners, trade-offs between goods and agriculture, moaning farmers, furious green campaigners, unhappy labour activists. Divisions among the EU member states, the European Commission deciding how far to push it. Vintage stuff. Someone alert the Walloons. Some thoughts:

What it says about the EU

This one is fairly obvious: Ursula von der Leyen is now showing she’s one of the most powerful commission presidents anyone can remember by trying to drive through a deal that divides the big member states, and on this occasion the French opposition isn’t just for show. This is the biggest preferential deal Brussels has ever done: the commission reckons it’s four times the economic size of the largest so far, Japan. There’s a lot of EU and von der Leyen credibility riding on this. If it fails to get ratified, following the freezing of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with China in 2021, it really looks as if megadeals with Brussels are off the table.

What it says about Mercosur

It’s even more impressive for Mercosur, which has never really functioned even as an internal market, has an unfortunate classic Latin American legacy of protectionist import substitution to overcome and has hitherto only signed small or thin external trade deals. It doesn’t exactly run on political consensus either. Its member countries are currently led by two leftists (Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in Brazil and Luis Arce in Bolivia, though Bolivia only joined Mercosur this year and is yet to implement all its rules), a conservative being replaced by a leftist (Luis Lacalle Pou being succeeded by Yamandú Orsi in Uruguay) a conservative (Santiago Peña in Paraguay) and whatever the hell Javier Milei now is in Argentina (take your pick between a libertarian, an anarcho-capitalist and a pragmatic conservative with some comedy rhetoric). Milei has threatened to leave the bloc (and isn’t the first to be frustrated by its lack of ambition), but not even he will trash a trading area just as it agrees a deal with one of the biggest markets on the planet.

Mercosur’s negotiators have got a bunch of substantive concessions out of the EU after the deal was reopened in 2019, including more protection for their car industries, loopholes in the rules about liberalising public procurement, and, in a sign of the times and following a precedent (sort of) set in an EU-Chile trade deal, some ability to divert critical minerals to domestic producers. Also a chunky €1.8bn in aid to help Mercosur producers adjust, especially to the deforestation regulation (see below). The EU, or the commission at any rate, wanted this deal, and the Mercosur countries knew it.

Deep in the forest

Another really notable Brussels concession is the commitment to use Mercosur countries’ own data when complying with the EU’s regulation blocking imports from deforested land, whose implementation has been delayed amid a deluge of complaints from foreign exporters (and indeed EU producers) about its complexity. The EU trade directorate’s irritation about the mishandling of the deforestation regulation (EUDR) by the environment directorate, which has the lead on it inside the commission, has become increasingly public. The former has now in effect used a trade deal to cut through the tangle created by the latter. Very cunning work. This will be watched closely in Indonesia and Malaysia, which are negotiating with the EU over their oil palm growers’ compliance with the EUDR. Turns out that the EU’s “autonomous” instruments can in fact be bargained over. Next stop: CBAM.

A buoy from Brazil

Particularly good work from Brazil, showing you’re more likely to get a deal with the EU if you’re a leader like Lula, able to display plausible environmentalist and workerist credentials, than a fire-breathing free marketeer like Jair Bolsonaro, his predecessor. Bolsonaro was super-keen on free trade, but the EU didn’t trust him to safeguard the Amazon. European green and labour campaigners are going to find it quite hard credibly telling a progressive international hero like Lula that he’s selling out Brazilian workers and trashing the planet. Still, I’m sure they’ll have a go.

The US, an anti-globaliser alone

The alleged worldwide backlash against globalisation is still largely notable by its absence. Europe is signing preferential deals, as is South America (noting again the varied political alignments of the Mercosur presidents), the Asia-Pacific including China, Africa, the Middle East, even India (albeit pretty thin ones in the latter case). Of course lots of governments are using various trade-restrictive tools, but the lack of political resistance to formal agreements is striking and there’s not much sign of trade itself imploding. The EU’s swing to the political right may have increased hostility to immigration and domestic green regulation but it hasn’t created an irresistible anti-globalisation backlash. The US is an outlier. Indeed, Washington’s pathological hostility to deals is an excellent reason for other countries to sign them to uphold the rules-based system and create trade routes outside America. The world’s trade negotiating function is very much alive, but it almost completely excludes the US — and, sadly, the WTO.

The comedy Brexit angle

Finally, least importantly but most amusingly, if this does get done it will be great fun watching the reaction among UK Brexiters. They’ve long said the EU is a moribund trading bloc which can’t do big deals, and by leaving it the UK could sign exciting agreements like that with the Asia-Pacific CPTPP. (The UK already had deals with the big CPTPP economies inherited from the EU, but details, details.) I guess the UK could always start its own talks with Mercosur, which if they replicate the EU ones will conclude in about 2050.

Charted waters

Sales of high-end £1,000-plus bottles of whisky have dropped sharply this year, apparently the bursting of a bubble caused by years of low inflation and low interest rates. I myself have bought very few £1,000 bottles of Scotch in the past 12 months.

Trade links

The Centre for European Reform examines the lessons from the early stages of the EU implementing its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

The FT’s TechTonic podcast looks at the geopolitics of AI semiconductors, the latest source of tensions in the sector. If you prefer reading, the transcript is here.

China’s manufacturing model may have run out of road.

Former Spanish foreign minister (and chief of staff to Pascal Lamy as WTO director-general) Arancha González argues in Politico that the EU needs a more robust response to the threat of US tariffs.

The FT’s State of Britain newsletter looks at the UK’s alleged reset of relations with the EU and finds a sense of internal paralysis inside the British government though some constructive thinking outside. It references a very interesting paper by former European Commission senior official Ignacio García Bercero for the Bruegel think-tank. (See also a paper Bercero wrote some years ago on whether the EU should soften its hard line on recognising foreign regulations.)

Trade Secrets is edited by Jonathan Moules

Source link