Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

Bill Clinton’s election strategist James Carville wanted his 1992 presidential campaign to focus on three simple messages. But one of them has transcended its original context: “It’s the economy, stupid.” What then to make of the decisive swing towards Donald Trump against a backdrop of low unemployment, falling inflation and economic growth rates most of the rich world would envy?

Do voters no longer care about economic performance? Or were they misinformed about how strong the US economy really is under Joe Biden? Or is there another explanation for why the Democrats presided over strong growth, yet lost?

Let’s take these possibilities in turn. Many people are so tribal in their political loyalties that their satisfaction with the economy depends almost entirely on who is in charge. You can see this in the sharp swings in sentiment whenever the presidency changes parties. For many years, it has been the case that when a Democrat is in the White House, registered Democrats are much more confident about the economy than registered Republicans. When a Republican is in charge, that pattern reverses.

The scale of these politically inflected shifts in sentiment is as large, perhaps larger, as that in response to actual economic events, such as the 2008 financial crisis, or the Covid-19-related contraction. In other words, when you ask people how confident they feel about the economy, they actually tell you how confident they feel about the president.

But it would be wrong to conclude that the actual performance of the economy simply does not matter to voters. For one thing, voters tell pollsters it matters very much indeed. In October, Gallup found that 52 per cent of respondents rated the economy as an “extremely important” influence on their vote for president. This is the highest percentage since 2008 and the highest of any issue this election. This suggests a puzzle. Americans voted decisively for change, yet most headline indicators suggest the US economy was doing well. Were the voters just misinformed?

The simplest metric for economic performance is real GDP growth, on which measure the US performance has been enviable. The US grew more than 10 per cent between the end of 2019 and the second quarter of 2024. The best of the rest in the G7, Italy and Canada, grew about half as much. The UK grew less than 3 per cent. Germany didn’t grow at all.

Or look at unemployment: the US unemployment rate fell to just 3.4 per cent at moments in 2023, the lowest level since the 1960s. Now it is a little over 4 per cent, still better than at any moment during the 16 years in which George W Bush or Barack Obama were in charge. Both were comfortably re-elected. If US growth is the envy of the developed world, even after adjusting for inflation, and unemployment is close to record lows, what sort of a fool would vote for change on economic grounds?

Perhaps it is the commentators who have been the fools. Look beyond the standard headline indicators and there are plenty of signs of economic stress. Jason Furman, who was a senior economic adviser to the Obama administration, has pointed to several. There’s the prime-age employment rate, which is the proportion of people aged between 25 and 54 who are employed. This indicator shows how many people are engaged with the labour market and it falls if people give up looking for a job, are too ill to work, or simply feel they have better things to do with their time than work for money. In the US, this rate has barely recovered to pre-pandemic levels. In the supposedly struggling euro area, it’s significantly up. Low unemployment rate notwithstanding, perhaps the US economy has struggled to satisfy the people most likely to feel they should have a job?

And while wages have grown faster than inflation, the trend has been much less positive since 2019 than it was in the years before. Real median household incomes have fallen since 2019, and the poverty rate has risen.

The FT’s Alphaville column has also spotlighted the soft underbelly of the US economy. They point out that while wages have, on average, grown faster than inflation, that may not be true for lower-income households. We’ve seen plenty of signs of “cheapflation”, a tendency of cheaper products to increase in price more than expensive varieties of the same good. The cumulative effect has not been small, and poorer households are almost certainly more vulnerable.

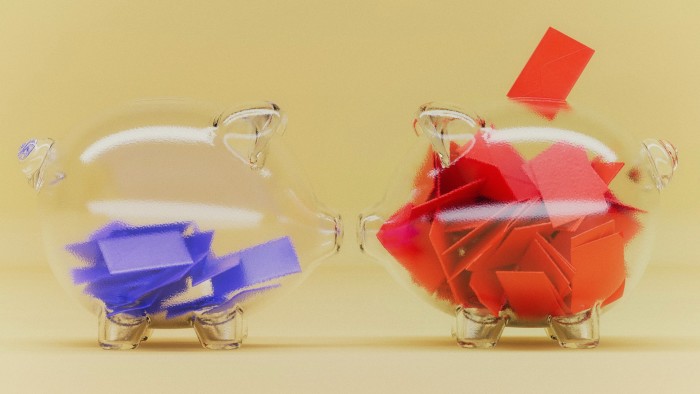

The point of all this? The economy is a complicated system and just because some things are going well for some people does not mean that everything is going well for everyone. And, in particular, not for swing voters on the issues that matter most to them.

Defenders of President Biden’s administration might reasonably point out that he has done his best to fix what weaknesses the US economy has, and even more reasonably point out that Trump’s medicine of mass deportations and ubiquitous tariffs is more likely to harm the patient than heal. Fine.

But if the question is “why didn’t American voters understand that the economy was doing brilliantly?”, the question itself is the problem. The economy has many facets and a strong economy for some does not mean a strong economy for everyone. With that in mind, it’s still the economy, stupid.

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen