Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

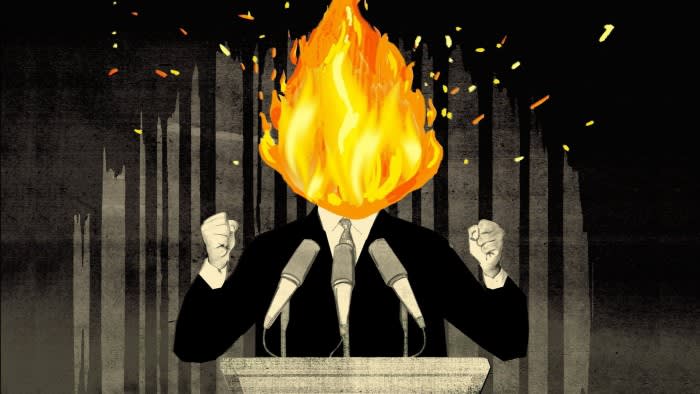

“Anger is right. Anger works. Anger clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit.” Well OK, Gordon Gekko was a money guy, so his famed Wall Street speech was about greed. Had he instead been a politician, he would know with equal conviction that, today, anger is the driving energy of politics.

It has always had a role. Oppositions need anger to drive out incumbents. But what perhaps is most striking about modern politics is that it has gradually become a permanent feature.

This is not to say that all the rage is irrational. Anger alone will not do the job unless it is linked to the right cause and the best of those is voters’ sense of falling living standards. Immigration is another, though in part it too is a function of economic dissatisfaction. Donald Trump won for largely conventional reasons, powered particularly by the high inflation of the Biden years. In the UK, Keir Starmer harnessed anger over inflation and public services. It would be a poor politician who did otherwise.

It is not absurd for voters to place more weight on their lived economic experience than those who quote the data at them. Similarly, Brexit looks foolish as a policy response. But viewed as a choice between the status quo and change, you can see why people who felt things were not working chose the camp which acknowledged their concerns.

Even so, across western democracies the anger carousel is spinning ever faster as like-minded movements learn from the Trump playbook. It is driven not only by politicians but by a partisan media ecosystem whose economic model depends on keeping their audience in a state of permanent mobilisation, fuelled by culture wars and paranoid hyperbole about enemy elites within. TV channels, podcasters, bloggers and websites need that constant crisis to maintain audiences. Confrontational rhetoric is incentivised with clicks. Why else has anyone heard of Lauren Boebert? And while the right is better at this, the left is also learning.

This has corrosive consequences that go way beyond election outcomes. In opposition it is easy. The enemy is the incumbent. But even in power the ecosystem must be fed enemies who provide alibis for failure. You need malign bureaucrats, woke elites, globalist financiers, partisan judges. Ultimately, this erodes belief in the entire system. Millions of Americans have, after all, just concluded that safeguarding democracy was less important than the other things Trump offers.

The anger carousel also loves binary issues which bind in supporters. Is it a coincidence that even when voters insist their central concern is the economy, so much discourse is ever more dominated by matters which lend themselves to an absolutist debate: Brexit, Scottish independence, abortion, trans-rights, gun control, immigration, Israel/Gaza, the retreat from net zero?

This leads to the othering of your opponents, to the dehumanising language of “deplorables” and “garbage”, of Marxists, fascists and treason. It also serves parties in electoral systems where the choice is binary and when complete power can be won with less than a majority of votes. This is not only a right-wing phenomenon but progressives, too prone to blinkered moralising, are less effective at it.

Is there a way past this? Only by finding ways to quell the anger. Clearly a vibrant economy is the best medicine, but only if it raises all boats. Boris Johnson’s levelling-up agenda proved empty, but the recognition that even in boom times too many areas were being left behind was a crucial insight.

But beyond that, the core duty must be taking seriously the concerns of the voters the other side is targeting. Some will always be beyond reach. But many need not be. Fighting the anger and the betrayal narratives means reconnecting with those who believe you have stopped listening to them. The opportunities grasped by the radical right come from identifying the ordinary voters progressives have left behind. The liberal elite was never a complete fiction.

One reason why Starmer won (aside from the immense help gifted him by the Conservative government) is that he paid attention to those voters Labour had lost, accepting their concerns on immigration and Brexit, and focusing on the economy, though some constraints may hobble his ambitions for growth.

Even if they draw back from Trump’s most egregious constitutional abuses, populist parties can see the electoral value of permanent anger, bolstered by a media and social media system with a vested interest in an approach which has little use for compromise or constructive opposition.

If this were only about who is up or down electorally it would matter less. But permanently mobilised anger is a threat to the stability of the system and quelling it is a democratic imperative.

Source link