The Federal Reserve is poised to lower its benchmark policy rate by a quarter-point next week, sticking to its course in the face of a distorted jobs report and uncertainty over economic policy beyond Tuesday’s US presidential election.

The Federal Open Market Committee will announce its next decision on interest rates two days after polls close, with the results potentially not yet known.

Officials are likely to press ahead with a quarter-point reduction, a resumption of a more traditional pace of easing after September’s larger than usual half-point cut. The move would lower the federal funds rate to a new target range of 4.5-4.75 per cent.

“You still have a federal funds rate in real terms that is quite high and they don’t want to overly slow down the economy, so it makes sense to continue to gradually decrease it unless conditions change,” said Eric Rosengren, former president of the Boston Fed.

Underpinning the decision is evidence that the US economy is growing solidly — buoyed by a healthy labour market and consumers who just keep spending — even as inflation falls. GDP rose 2.8 per cent on an annualised basis in the third quarter, slightly less than the previous period but still indicative of a healthy expansion.

One blemish was Friday’s jobs report, which showed payroll gains of only 12,000 for October, marking the worst month in Joe Biden’s tenure as president.

The figures were skewed by two hurricanes that hit the US south-east around the same time the Bureau of Labor Statistics was beginning to collect the data. Worker strikes, including one that is continuing at Boeing, accounted for another 44,000 jobs being cut for the month.

Most economists expect jobs growth to rebound, with little sign that October’s lacklustre gains are a precursor to acute weakness.

“The recession story has petered out completely now,” said James Bullard, who left his post as president of the St Louis Fed last summer to become dean of Purdue University’s business school. “That is consistent with the idea that the committee would want to go slowly as they reduce the policy rate going forward.”

The question dogging officials is how quickly to get to a neutral level of interest rates that no longer suppresses growth but does not stimulate it either. The goal is to get inflation back to the long-standing 2 per cent target, a task that looks increasingly plausible without outsized job losses.

As of September, the personal consumption expenditures price index fell to 2.1 per cent, although a “core” measure that strips out volatile food and energy items and is the Fed’s preferred gauge of underlying price pressures is still elevated at 2.7 per cent.

Fed officials have in recent weeks endorsed a gradual reduction in borrowing costs, suggesting a redux of September’s half-point cut is not seen as necessary. But they have yet to provide specificity about what that means in practice.

“People have been trying to define the word ‘gradual’. Is it every other meeting? Is it every meeting? I think right now it’s code for not 50 [basis points],” said Esther George, who retired as the Kansas City Fed president in 2023.

George cautioned her former colleagues to be “careful”, given they are “easing conditions at a time when you can still see inflation risk”.

“Yes, the [inflation] rate has come down, but it’s been hanging out in the 2.5-3 per cent range, and the upside risks to me look like they are becoming more noticeable,” she added.

Seth Carpenter, who spent 15 years at the Fed and is now the chief global economist at Morgan Stanley, also sees scope for inflation to “stall out” and settle above 2 per cent. As such, he forecasts the Fed to proceed with a quarter-point cut at next week’s meeting as well as in December, and then deliver further reductions until it reaches a level just above neutral — at about 3.25 per cent.

“Inflation really is first order here,” he said. “If things are not fine with inflation, then the jobs data really matter a lot in terms of skipping a cut.”

Looming large over the Fed’s meeting next week and its future gatherings is the US presidential election. Both candidates have sketched out very different economic platforms, which if implemented could alter the outlook for growth and inflation in a material way.

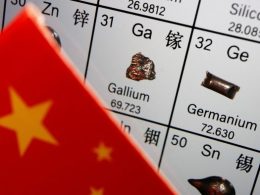

Former president Donald Trump has touted a return to more protectionist trade policy with the imposition of a sweeping set of tariffs, in addition to lower corporate taxes and a crackdown on immigration. He has also signalled his preference to have a greater say in the Fed’s monetary policy decisions — a worrisome incursion on the institution’s long-held independence if realised.

Vice-president Kamala Harris, meanwhile, has focused on expanding the country’s social safety net, paid for by higher taxes on the wealthy, while upholding the Fed’s independence.

Initial analysis from most economists suggests that Trump’s plan would be more inflationary than Harris’s and could also dent growth. But what policies are actually enacted — and in turn their economic impact — will depend chiefly on how power is divided among both chambers of Congress.

Against this backdrop, Rosengren said he did not expect chair Jay Powell to signal too strongly the policy path forward at next week’s meeting.

“You don’t want to give guidance if you’re pretty uncertain about what the outcome is going to be,” he said.

Source link