From plotting to kill Cuba’s communist leader Fidel Castro with a poisoned milkshake, to staging a CIA-backed coup against Guatemala’s elected government, the US has made many attempts to reshape its “back yard” — often with unintended consequences.

President Donald Trump’s deployment of a large military force off Venezuela to unseat revolutionary socialist leader Nicolás Maduro has reawakened memories of America’s history of “gunboat diplomacy” in the region.

John Coatsworth, a historian at Columbia University, has counted at least 41 successful US interventions to change governments in Latin America between 1898 and 1994.

“The option to depose a sitting government has appeared on the US president’s desk with remarkable frequency over the past century,” he wrote.

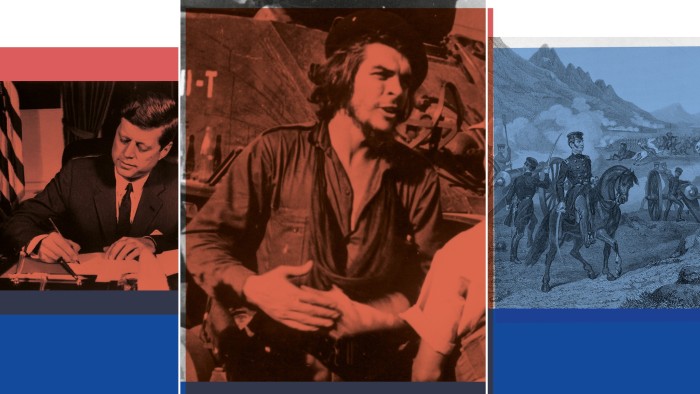

The most consequential American military intervention was one of the first: the invasion and seizure in the 1840s of more than half of Mexico’s territory, including the present-day states of California, New Mexico, Arizona, Texas, Nevada and Utah. That war has left a deep and lingering scar on the Mexican psyche.

Trump said the attack on Venezuela was needed to combat drug trafficking and narco-terrorism, which threaten US national security. He added that US companies would be able to do deals in oil-rich Venezuela. The move also sends a message to Maduro’s Russian and Chinese allies that the US wants them out of its “back yard”.

Victoria Murillo, director of the Latin American Studies institute at Columbia University, said Trump’s move on Venezuela only made sense if viewed as “about opportunities for US companies . . . so that US companies get access to Venezuelan oil: old-fashioned imperialism in the economic sense”.

That would echo some past US military interventions. In the early 20th century, US troops occupied various Central American and Caribbean nations in what were known as the “Banana Wars” to further the interests of US companies such as United Fruit — today’s Chiquita — and Standard Fruit, now Dole.

Nonetheless, Alan McPherson, a history professor at Temple university in Philadelphia, said Trump’s use of military force to blow up small speedboats in the Caribbean and Pacific said to be carrying drugs, killing the civilians inside, was without parallel. “Even in the long and violent history of US military occupations, these are unprecedented moves.”

One of the most active American interventionists was William McKinley, a US president who Trump admires because he “made our country very rich through tariffs and through talent”.

McKinley annexed Hawaii, acquired Puerto Rico and the Philippines, pushed Spain out of Cuba and set the stage for the US to build the Panama Canal before he was assassinated in 1901.

This century, China has vastly expanded its trade and investment footprint in Latin America, and Trump has made no secret of his desire to push Beijing out of a region he sees as a sphere of US influence.

This mirrors Washington’s obsession in the cold war with preventing the spread of Soviet and Cuban influence. That led to the US supporting military regimes in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay that tortured and executed leftwing opponents. CIA information and training helped Bolivian troops locate and kill Argentina’s Cuban-allied revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara in 1967.

A 1982 CIA report on Moscow’s activity in Latin America, now mostly declassified, points to how “the Soviets have by and large successfully implemented a policy of encouraging unrest in various Central American states . . . and improving their relations with the governments of the more important South American countries”.

“Over the next few years, Soviet efforts to gain influence are likely to increase,” it concluded.

Washington eventually achieved its cold war objective of stopping Moscow, although it brought the world close to nuclear war during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis.

“Militarily it’s clear that the United States won the cold war,” said McPherson. “They really only accepted that dictators leave power in places like Chile, Argentina, Brazil, once the opponents of the dictatorships could show that they were going to sideline the communist groups in their coalitions.”

But the price was an American reputation sullied by association with brutal dictatorships — a point not lost on today’s adversary China. The US has held sway over Latin America by “unscrupulously launching coups, invasions and sanctions wherever necessary”, said state news service Xinhua in a recent commentary.

Although Trump has backed his rightwing allies in El Salvador, Argentina, Ecuador and Paraguay, his aggressive use of military force and tariffs elsewhere has upset other Latin American nations.

“Things are very tense,” said a senior diplomat from the region based in Washington. “There’s a feeling of abuse, that Latin America has no role to play, no government worth talking to. It’s never felt more like the back yard. This will not end well.”

That said, US interventions have not been universally unpopular. Jorge Castañeda, a Mexican historian and former foreign minister, noted Latin American business leaders and conservatives often backed America’s moves because they shared Washington’s dislike of socialism.

“I would always qualify the mantra about how Latin Americans hate US intervention, they’re always opposed, and if the US were to do this, it would do terrible damage,” he said. “Some Latin Americans are always opposed and think it would do damage, but for others it wouldn’t.”

American attempts at overthrowing Latin American governments have a chequered history. Among the best-known is the disastrous Bay of Pigs episode in 1961, when a CIA-funded army of Cuban counter-revolutionaries came ashore to overthrow Fidel Castro and was defeated in two days.

After that debacle, Washington adopted a covert programme codenamed Operation Mongoose to destabilise Cuba, including numerous failed attempts to assassinate Castro.

According to a Cuban intelligence chief, the closest the CIA came to killing Castro was a 1963 attempt with poison that was to be slipped into the Cuban leader’s daily milkshake. The plot failed because the poison capsule stuck to the freezer of the café where it was hidden and burst open when the waiter tried to retrieve it.

Castro died in 2016 at the age of 90, after handing over power to his brother Rául. Cuba’s communist regime endures to this day.

Joseph Ledford, a historian at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, concluded “the number one thing that policymakers should take away from the history of US interventions in Latin America is the problem of unintended consequences”.

Those who intervened “did not have an understanding of, or an appreciation of the long-term ramifications of such interventions. It would take a lot of effort by their successors to undo the damage.”

Source link