The process of merging companies involves a lot of euphemisms designed to make things sound duller than they are, like synergy, antitrust remedy and goodwill impairment. That alone is what makes “hostile takeover” a great brand. It has drama.

Unfortunately for a general audience, the drama is rarely sustained. Most hostile approaches either fizzle out or result in a friendly resolution after a bit of arguing over price. Reaching the denouement of mutiny by shareholder vote hardly ever happens, so to really enjoy the hostile takeover process a person has to be into its slow-moving corporate kabuki theatre of regulatory arbitrage and shadow boxing by legal precedent.

Fortunately, we are. Here in no particular order is FT Alphaville’s historical top-10 outbreaks of corporate hostility:

Charles Clore vs J Sears & Co (1953)

Most histories of the hostile takeover start with the US corporate raiders. This is Charles Clore erasure.

Clore (1904-1979) was the son of an east London tailor who made his first fortune as a property speculator. After UK planning controls were relaxed in 1949, in an effort to spur postwar development, Clore began to target companies with undervalued freeholds on the balance sheet. He failed with hostile offers to buy Frederick Gorringe, a department store on Buckingham Palace Road, and the Grosvenor House Hotel on Park Lane.

J Sears & Co, best known at the time for its chain of Freeman, Hardy and Willis shoe shops, proved a softer target. The Sears family had to sell a large percentage of their shareholding in 1953 to pay death duties, which allowed Clore to seize control by majority vote and appoint himself as chair. Clore then put most of the shoe shop freeholds on sale-and-leasebacks, rolling the profits forward to finance more deals including his purchases of Selfridges department store and jewellers Mappin & Webb.

Journalist Harold Wincott approved, using his FT column in 1953 to argue that hostile takeovers like Clore’s were a valuable corrective for politicians who wanted to impose dividend caps and company directors who viewed shareholders as a bit of a nuisance.

“Natural forces always do win out in the end, and all that is happening now is that directorial pants which have been sitting on the safety valve for a decade or so are at last getting scalded”, wrote Wincott. The “true interests of the country would have been far better serviced if shareholders had had the profits and reinvested them at their discretion.”

The episode is chronicled by Andrew Johnston in this recent paper for Cambridge University Press.

Louis Wolfson vs Montgomery Ward (1955)

To suggest that Louis Wolfson (1912-2007) invented the modern US proxy campaign would be wrong. What he pioneered was fighting dirty. Wolfson would send pamphlets and open letters to small shareholders that sought to channel any latent disgruntlement and build voting blocs big enough to dislodge the incumbent board.

Wolfson’s biggest victory came in 1951 with the takeover of NYSE-listed Merritt-Chapman & Scott, a blue-chip marine engineer he first turned into a conglomerate, and then into a bankrupt conglomerate. His biggest defeat came four years later, when shareholders of retailer Montgomery Ward chose to stick with Sewell Avery, its octogenarian chair. Avery retired soon after, claiming moral victory.

As well as setting a template for a generation of corporate raiders to use the power of persuasion, Wolfson’s brash approach led to a tightening of US securities law around what’s permitted during a hostile takeover.

Wolfson’s legacy is well known, in part thanks to his many run-ins with enforcement agencies in the subsequent decades. What might be overlooked is how funny it all was at the time. The New Yorker in 1955 ran a long dispatch from Ward’s shareholder meeting by John Brook that’s likely to be among the best pieces of on-the-ground financial reportage you will ever read.

Mesa Petroleum vs. Cities Service Company (1981)

No fiction writer would dare name their corporate raider T. Boone Pickens. A geologist by training, Pickens (1928-2019) used his public image as a straight-talking Texas oilman to turn Mesa Petroleum, the explorer he co-founded, into a leveraged buyout vehicle.

Starting with a hostile offer for Hugoton Production Company in 1968, Pickens used the strategy of buying sizeable minority stakes in target companies much larger than his own. LBOs were made possible by a burgeoning market for junk bonds, with sales organised by Michael Milken at upstart investment bank Drexel Burnham Lambert.

Where Boone Pickens really excelled was not buying companies.

In 1981, Mesa made a hostile offer to buy Cities Service Company. Cities Service responded by making a hostile offer for Mesa (the so-called Pac Man defence). Cities Service agreed to sell itself to a white knight bidder, Gulf Oil, then to Occidental after that deal fell through. By losing out, Mesa banked a $30mn profit on the sale of its Cities Service stake.

Boone Pickens repeated the trick by building a stake in Gulf Oil and launching a hostile offer, which spooked the company into offering to buy him out at a “greenmail” premium. He rejected the offer, which meant Mesa netted around $720mn when Gulf Oil eventually merged with Socal Oil. Mesa’s hostile offers for Phillips Petroleum and Unocal delivered very similar outcomes. Win-win!

Carl Icahn vs. Trans World Airlines (1988)

Like the dog who caught the car, Carl Icahn appointed himself chair of Trans World Airlines in 1988 after orchestrating a hostile LBO that lumbered it with $1bn in debt.

Fellow corporate raider Frank Lorenzo had been looking to acquire TWA and Icahn, a 20 per cent shareholder, was put forward as a white knight buyer by the unions. What happened instead was that Icahn sold key assets including TWA’s London routes in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to stave off bankruptcy, which duly arrived in 1992.

Before stepping down as chair in 1993, Icahn set up an agreement that allowed him to buy an unlimited number of TWA tickets through St Louis for just 55 cents in the dollar. He then created lowestfare.com, sold discounted TWA tickets at a reported cost to the airline of $100mn a year, and drove it into bankruptcy again in 1995.

AT&T vs NCR (1991)

“Worst ever hostile takeover” is a competitive category.

ABN Amro’s purchase by Royal Bank of Scotland and partners in 2007 is an obvious contender, as going over the top meant the consortium was unable to run a proper due diligence process, though it can’t be known if access to the books would have made RBS CEO Fred Goodwin see sense. AOL’s infamous tilt at Time Warner in 2000 was hostile only briefly, with the companies switching to mutually assured destruction by merger of equals.

We’ll go instead for AT&T’s attempt to revive its hardware division by buying NCR (né National Cash Register) for $7.4bn in stock. NCR boss Charles Exley initially said no, rejecting the offer as grossly inadequate and apparently believing the US should value its foothold in a computing industry that at the time was dominated by the Japanese.

NCR shareholders including Steve Cohen wrote op-eds about how unfair this policy was, so AT&T went direct with a tender offer to shareholders, Exley eventually abandoned what he called “the Greta Garbo defence” in exchange for a 30 per cent higher price.

There’s no doubt AT&T got hustled. It had been NCR’s biggest customer, and the change of ownership caused sector peers to cancel orders because they didn’t want a competitor as a supplier. Taking control just created a more direct way for AT&T to subsidise NCR growing losses. The division was spun off in 1996 at a valuation of about half what AT&T had paid.

The Greta Garbo defence became more commonly known as the Nancy Reagan, after the First Lady’s “just say no” anti-drugs campaign.

MacAndrews & Forbes vs. Revlon (1986)

US takeover law was rewritten to allow an objectively terrible hostile takeover of Revlon by MacAndrews & Forbes, Ronald Perelman’s cigars-to-cars conglomerate.

Revlon had tried nearly every shark repellent strategy available, including adopting a poison pill and agreeing to a white-knight takeover that in effect blocked Perelman from making a higher offer. But Perelman eventually won the bidding war after the Delaware Supreme Court said Revlon’s strategy wasn’t fair and stuck down its defences.

Once a company is up for sale or breaking apart, the fiduciary duty of directors changes from defending corporate priorities to extracting the highest value reasonably available to shareholders, the court ruled. The principle in US law that a boards shouldn’t stand in the way of the highest bidder is still known as Revlon duties.

On completing the deal, Perelman immediately sold off several Revlon divisions not related to cosmetics to help meet LBO debt payments. Regular guttings of management and countless acquisitions later, Revlon still rarely turned a profit and, having limped along under a heavy debt burden for nearly two decades, entered bankruptcy protection in 2022.

Granada vs. Forte (1995)

Forte owned hotels including London’s Café Royal and Plaza Athénée in Paris, as well as the Harvester and Little Chef restaurant chains. Granada owned regional TV franchises, some motorway service stations and a Camelot-themed fun park in Lancashire.

Gerry Robinson, Granada’s CEO, launched its hostile offer four years after Rocco Forte had inherited the business from his father. Robinson told shareholders he would pay a special dividend funded by selling most of Forte’s upmarket hotels. Forte responded by seeking buyers for nearly everything other than the hotels, while setting loose a swarm of lawyers and PR people. (The tactic is known in the US as killer bees.)

The mudslinging lasted months. Forte shareholders sided with Granada’s £3.9bn offer, believing it offered more certainty, and Robinson began dismantling the group. Finding buyers proved less easy than he predicted, however, so Granada was still an odd jumble of stuff when it merged with contract caterer Compass in 2000 and split in two. Forte was given the family name back as a very belated gesture of goodwill.

Porsche vs. Volkswagen (2008)

Who could forget The Fruit Machine? Just as the Great Financial Crisis was getting started, Porsche thought it was smart to quietly buy shares and options accounting for 74 per cent of Volkswagen’s voting rights.

VW became the world’s biggest company, at least for a day, as short sellers betting on a discount narrowing between VW ordinary and preference sales were squeezed out. The need to cover outstanding options destroyed Porsche’s balance sheet, leading to its eventual bailout by VW. Here’s a Jamie Powell post that explains the whole scene.

Elon Musk vs. Twitter (2022)

This one’s contemporary enough not to need too much explanation.

Elon Musk, the world’s most expensive person, made an unsolicited offer to buy Twitter at a price per share that sounded like a joke but apparently wasn’t. After showing a bit of resistance, Twitter’s board conceded that the best course of action for shareholders was take Musk seriously and agreed to sell the company at the not-a-joke price. Musk then admitted he didn’t want to buy Twitter and spent around a year trying to wriggle out of the deal, but Twitter’s board refused to let him, so Musk is now lighter by $44bn and has a website for a personality.

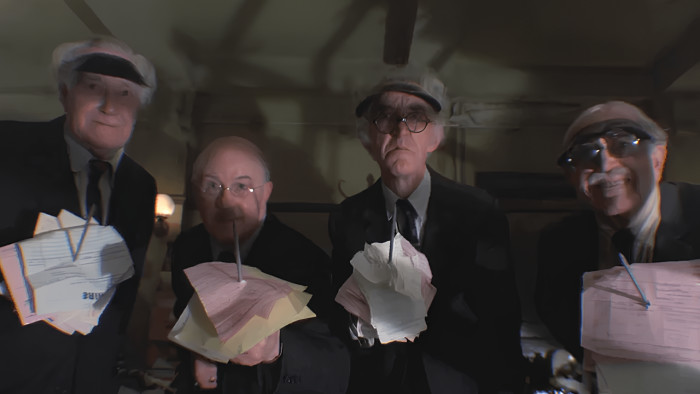

The Permanent Assurance Company vs. the Very Big Corporation of America (1983)

Terry Gilliam’s short film tells of employees at a City of London insurance company who rebel against US management following its acquisition, then sail an office block across the Atlantic to launch a hostile attack on the new owner’s Wall Street headquarters. The strategy forms a template for further hostile acquisitions that ends abruptly when the office block sails off the edge of the world.

In takeover terms, the strategy is perhaps most similar to a buy-in management buyout, or Bimbo, in which an internal management team raises external LBO funding and pursues a group-wide change of direction. We can’t think of any real-life examples of hostile Bimbos so if you can, please tell us in the comment box.

TBC: Paramount Skydance vs. Warner Bros Discovery (2025)

The hostile offer from Paramount to buy WBD is shaping up to be a typical of the genre: lots of drama at the start, followed by a lot of talking. WBD agreed to sell itself to Netflix after a long auction process. Paramount called shenanigans, saying the offer it made to WBD was superior because it gave shareholders more regulatory certainty and more cash upfront, and launched a tender offer for WBD stock.

“It’s a classic power play — or as Succession fans might say, a bear hug reminiscent of Kendall Roy’s boardroom manoeuvres,” reports Xposure magazine, incorrectly, since a bear hug by definition has to involve a hostile offer at a significant premium to the market price.

It’s also likely to be wrong with regards the pacing of the drama. There’s a high probability of more bidding rounds, then regulatory clearances, and it’s in everyone’s immediate interest to sound happy with the outcome. Unlike Succession, Paramount-WBD will almost certainly drag on for longer than the average person can maintain interest. It’s only years later that the audience gets resolution by schadenfreude.

Have we missed your favourite? Tell us below.

Source link