Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

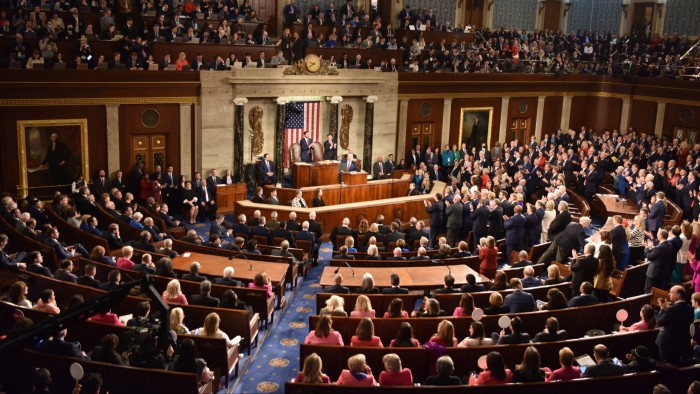

This week saw a rare and extraordinary thing: congressional Republicans standing up to Donald Trump on trade. Five of their senators voted with the Democrats to oppose Trump’s 50 per cent tariffs on Brazil, and four to overturn his import duties on Canada, both among his most ridiculous acts of protectionism in a crowded field.

The votes will have zero effect. The initiative will fail in the House of Representatives, whose cowed Republican Speaker Mike Johnson habitually does Trump’s bidding. They would need two-thirds majorities to overcome a presidential veto in any case.

As I discuss with trade law professor Jennifer Hillman in the FT’s Economics Show podcast, the Supreme Court will next week hear Trump’s appeal against lower courts’ rulings that his routine use of “international emergency” tariffs usurps congressional authority. But it apparently takes the judicial branch to defend the legislature’s prerogative, because lawmakers — and very particularly the Capitol Hill Republicans — are too scared to assert it themselves.

Trump’s second term is showing the limits of the courts in restraining the use (and abuse) of executive power. Even if the Supreme Court ignores Trump’s bullying — he is warning them about causing economic ruin and threatening to attend the hearing — and upholds the lower courts’ rulings, it won’t necessarily restrain him for long. By using other tariff powers designed to prevent balance of payments crises, promote national security and punish unfair trade, Trump can resurrect much of the existing wall of duties.

Congress could also act to restrain these, but again it would need broad bipartisan support to overcome a veto. The judiciary cannot substitute for the legislature.

The feebleness of the congressional Republican caucus regarding Trump isn’t news. But it’s particularly egregious given how emphatically the US constitution gives the legislature control over trade. It’s right there in Article I, which states that Congress has the power to “lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises”, and “to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations.”

More recently Congress delegated some power to the executive, notably in the Trade Act of 1974. But it still required the presidency to obtain specific authority to negotiate deals, sometimes micromanaged their content and was quite happy to hold up or refuse ratification even after signature.

In 2007, Congress forced then-president George W Bush to include some most un-Republican commitments to promoting labour and environmental standards in trade deals. But in those days, trade policy was largely conducted through formal legally binding preferential trade agreements. Aside from updating an existing trade deal with Mexico and Canada in his first term, Trump prefers to cast around for whatever emergency executive powers might be lying about, which requires Congress actively to restrain him. This it has dismally failed to do.

During that first term, a heavily watered-down nonbinding bill saying the president should seek congressional approval before using so-called “Section 232” national security tariffs passed the Senate, but the Republican leadership in the House of Representatives prevented it from even being discussed. Since then, resistance to arbitrary presidential trade policy has not been aided by Joe Biden maintaining much of the Trump pathology, including the Section 232s, as a bogus rationale for outright protectionism. It doesn’t help that the Democrats in Congress over the decades have developed a visceral aversion to open trade.

These days, a metaphorical MRI of the Republican congressional caucus shows virtually no remaining evidence of a spine. Jennifer Hillman has helped to write a brief to the Supreme Court on behalf of members of Congress, which lays out the absurdity of the administration’s argument. For the justices to agree with Trump requires them to argue with a straight face that the word “regulate” can have entirely different meanings within the same phrase in a particular statute. And yet while the brief was signed by more than 200 Democratic senators and representatives, only one single solitary Republican put her name to it — Lisa Murkowski, senator from Alaska, who is in any case contemplating leaving the Republican caucus and becoming independent.

Other court briefs opposing the Trump position are signed by a grand list of Republican policymakers from decades past, including former senators. But it seems Republican bravery correlates strongly with current or incipient retirement. Two of the five Republicans who voted against the Brazil tariffs this week, former Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell and Thom Tillis of North Carolina, have already announced they will not stand for re-election. The vast majority of their colleagues have stayed meekly silent.

Since he was elected, only two forces have really caused Trump to recoil from his tariff campaign: the stock markets, which dropped rapidly after he announced the “liberation day” tariffs on April 2, and the threat of retaliation from China, notably its restrictions over rare earth exports. The founding fathers who wrote the US constitution probably didn’t envisage New York equity traders and the Chinese Communist party emerging as the most effective checks and balances on US executive power, and yet here we are.

Make no mistake: the Supreme Court decision on Trump’s tariffs is a hugely important moment, with implications for executive power way beyond this particular case. But the judiciary cannot by itself return trade policy to the realm of constitutional normality. That relies on the reassertion of authority by Congress to which power over tariffs was originally given and which it has wilfully allowed to slip away.

Source link