Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“Consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production.” Thus taught Adam Smith. It is hard to see what else production is for, now or in future. Consumption must be the goal of international trade, too. But what happens if significant players do not seem to believe this? Then the global system malfunctions.

The starting point here needs to be with a proposition fundamental to the economics of John Maynard Keynes: actual spending activates potential savings. Moreover, he argued, there is no reason to believe that the needed spending will happen naturally. He called this “the paradox of thrift”. Sustaining high levels of activity may demand policy action.

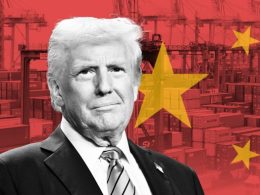

Today, the structural excess savings of a number of economies, notably China, Germany and Japan, are largely offset (and so activated) by the excess spending of the world’s most creditworthy country, the US, (and, to a lesser extent, the UK). The figures are startling. Just these big three surplus economies ran aggregate current account surpluses of $884bn in 2024. The surpluses of the top 10 countries amounted to $1.568tn. But surpluses are only made possible by deficits. Thus the US ran a current account deficit of $1.134tn, to which the UK added $123bn. (See charts.) Donald Trump’s presidency is, in part, a symptom of this reality.

Yet this is also peculiar. The excess savings of surplus countries are not being absorbed, as they were in the late 19th century, by investment in dynamic emerging and developing countries. They are offset instead by borrowing by the world’s richest country. Moreover, at least since the financial crisis of 2008, the domestic counterpart of this borrowing is not funding of the private sector but borrowing by the government.

Prior to the 2008 financial crisis, domestic spending had predominantly been driven by credit-fuelled property booms. These phenomena were not unique to the US, though the US has long been the biggest global borrower. In the Eurozone and the UK, too, net borrowing by the countries with huge current account deficits, before the financial crisis, was largely driven by credit-fuelled property bubbles (as in Ireland or Spain) or fiscal deficits (as in Greece). When those property bubbles burst and financial systems crashed, the consequence was also huge fiscal deficits almost everywhere.

In sum, we now seem unable to turn surplus savings in some countries into productive investment elsewhere. One of the reasons for this is that the countries able to borrow sustainably from abroad have creditworthy currencies. This rules out most emerging and developing countries. It also, it turned out, mostly ruled out deficit members of the Eurozone. In such a world, it is hardly surprising that the dominant borrower and spender is the US government. But is that a good result of the liberalisation of the global capital accounts? Hardly! It is a huge failure that all these surplus savings are frittered away in this way, rather than invested in productive activities, above all in poorer countries.

Moreover, the deficit countries are quite unhappy with this arrangement. Yes, they can spend more than their aggregate incomes. But they are hardly grateful. Not least, if a country runs a large trade deficit, it will consume more tradeable goods and services than it produces, since its residents cannot import non-tradeables without travelling. So, in deficit countries, manufacturing, a central part of the tradeable sector, is smaller than in surplus countries, where the opposite is true. This point, made by Beijing-based Michael Pettis, helps explain soaring US protectionism and so Trump’s trade war. The latter may be chaotic, indeed irrational, but its origin is not hard to identify: manufacturing matters, politically and economically.

Alas, the result is not even that good for countries with surplus savings either: Japan is a salient case. In order to reduce its current account surpluses in the 1980s, under US pressure, it pursued ultra-easy monetary policies, to grow domestic demand. This fuelled an unsustainable property bubble. When that popped in 1990, Japan suffered a financial crisis, feeble private sector demand, prolonged deflation and huge fiscal deficits. Arguably, it has never recovered. Amazingly, but not all that surprisingly, Japan’s net public debt has exploded, from 63 per cent of GDP in 1990 to 255 per cent last year.

China, not dissimilarly, had to eliminate much of its excess savings after the 2008 financial crisis made the huge US deficits and Chinese surpluses of the early 2000s unsustainable. After 2008, China too blew a huge property bubble and credit and investment boomed. It is now suffering from the aftermath, which includes weak domestic demand, low inflation and large fiscal deficits.

Germany was relatively protected by membership of the Eurozone. But the Eurozone financial crisis was also a natural outcome of its huge external surpluses. Since then the Eurozone has solved its post-crisis problems by becoming more like Germany: previously it had roughly balanced external accounts. But today, it, too, has become a sizeable net exporter of capital.

The biggest problem with Trump’s international economics is that he focuses on a symptom, the US trade deficit, and seeks to eliminate it through erratic and irrational tariffs. This may have been made a little less damaging by this week’s “deal” with China and resulting decline (perhaps temporary) in bilateral tariffs. But without macroeconomic rebalancing, the US trade deficits will remain. A necessary condition for this is to slash US fiscal deficits, along with policy changes elsewhere, notably China, aimed at lowering excess savings.

Saving is a good thing. But one can still have far too much of it sometimes.