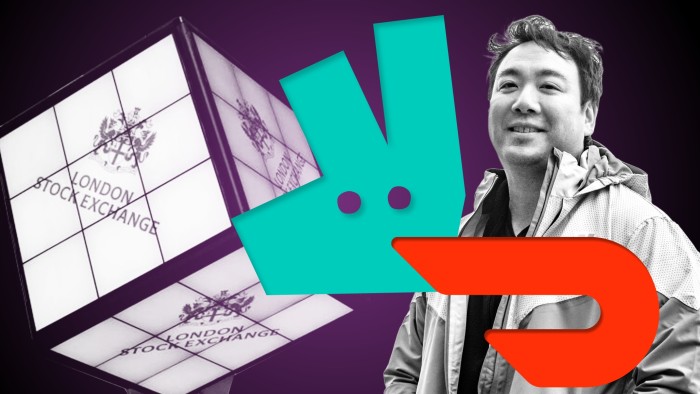

Deliveroo’s £7.6bn listing in March 2021 was hotly anticipated, but after just one day of trading the flotation was derided by one of the company’s own bankers as “the worst IPO in London’s history”.

Four years later, the food delivery business is set to be swallowed by its US rival DoorDash at less than half that valuation.

The announcement on Tuesday of a £2.9bn takeover, subject to a shareholder vote, signalled an end to Deliveroo’s rollercoaster ride on London’s public markets. It also renewed questions about the UK’s ability to attract and retain listings of large tech groups in the face of New York’s dominance.

“With the benefit of hindsight, it should have listed in the US,” said Hussein Kanji, founder of Hoxton Ventures, an early investor in Deliveroo. “I am super delighted we had the chance to seed Deliveroo but it’s a good example of the cost of not winning the US [delivery] market.”

The takeover, which follows US private equity group Thoma Bravo’s £4.3bn take-private deal last year for Darktrace, another homegrown UK tech group, underlines the challenge facing London’s stock market.

The London Stock Exchange last year suffered its worst year for departures since the financial crisis, while a moribund international IPO market has meant the companies exiting have not been replaced.

Giles Thorne, analyst at Jefferies, said Deliveroo had done “everything right” but was the latest in a “long succession” of UK-listed companies to be snapped up “cheaply” by larger American groups.

“They consistently set guidance that they met; they had a good balance sheet. They did everything that was asked of them, and still they weren’t rewarded — and that’s alarm bells,” Thorne said of Deliveroo.

“We’re excellent at supporting tech business at the start-up and scale-up phases, but not in supporting those same businesses . . . post-IPO,” he said, adding that there was too much “cynicism” among UK investors.

Some tech groups, such as fintech Wise, which has a market capitalisation of £10.6bn, remain listed in London. But other high-growth groups, such as Revolut, have signalled they are likely to look to the US for any future IPO.

Will Shu, Deliveroo’s chief executive, was inspired to start the company after resorting to late-night supermarket trips for his dinner while he worked as an investment banker at Morgan Stanley.

As a private start-up, Deliveroo was held up as a prime example of how a new breed of UK-based tech entrepreneurs were rivalling Silicon Valley in innovation and ambition.

The company launched in 2013 — a few months before DoorDash went live in the US — and went on to raise more than $1.5bn in private capital from venture investors such as Accel, Index Ventures and DST Global. Amazon also backed it, in what at the time was one of the US ecommerce group’s biggest start-up investments.

Shu first met DoorDash chief executive Tony Xu at a San Francisco coffee shop about a decade ago as the pair built their delivery businesses on opposite sides of the Atlantic.

While both companies expanded rapidly, it was DoorDash that emerged as an industry leader, helped by a blockbuster New York IPO in which its shares rose 86 per cent on their first day of trading in 2020. By the time Tuesday’s takeover was announced, its market capitalisation was nearly 30 times Deliveroo’s.

By contrast, Deliveroo’s shares plunged by 26 per cent on its first day of trading. Its stock never recovered as its growth rate slowed post-pandemic, while investors shifted their focus to more profitable companies when interest rates rose.

Key investors at the time said they would not invest in Deliveroo’s float because of its dual-class share structure, which gave Shu the power to block a takeover for three years. Such structures were common in the US but frowned upon by some UK investors and governance experts. Some also cited the company’s treatment of workers.

The company’s struggles on the London market were a disappointment after then-chancellor Rishi Sunak called the company a “true British tech success story” following its decision to list in Britain.

Some investors argue that Deliveroo’s leadership was led astray by promises from the then-UK government, which had hoped the company would kick-start a rush of new tech listings in London.

“This is what listing in London and listening to Number 10 and their false promises gets you,” said one UK tech investor.

Despite the fall in valuation, Shu said on Tuesday that he was “proud of what we’ve achieved”. The executive, who in the early days was also the company’s first delivery rider, added that the deal would give the business “additional firepower”.

Deliveroo’s first annual net profit of £2.9mn earlier this year was overshadowed by speculation, which the company denied, that Shu was planning to step down.

DoorDash had approached Deliveroo about a deal last summer, the Financial Times previously reported. But this year, the timing was right.

The acquisition in February of rival Just Eat Takeaway by investment group Prosus helped provide a catalyst for a deal. It left Deliveroo and DoorDash a limited window to strike a deal of their own before Just Eat grew stronger fuelled by its new owners, the person said.

Leaders at the companies on Tuesday said they had not decided whether Shu would have a role after the merger. DoorDash shares closed 7.4 per cent lower on Tuesday, while Deliveroo shares edged up to 175.4p — close to the 180p offered by its suitor.

For DoorDash, the deal offers the opportunity to boost its international scale. The San Francisco-based group also announced on Tuesday that it planned to buy restaurant booking platform SevenRooms for $1.2bn. It bought Finnish delivery app Wolt in 2021 for €7bn.

Sean Kealy, analyst at Panmure Liberum, said Deliveroo’s disappointing time on the public markets owed to external factors such as the tailing-off of heightened demand during the Covid-19 pandemic and regulatory concerns, such as over its treatment of riders.

Kealy pointed to the growth in the value of transactions completed on the app, which fell from 70 per cent in 2021 to 7 per cent in 2022: “The end of lockdown took the growth away and some of the regulatory issues got worse . . . All of these things combined meant the future prospects of the company looked very different to at the time of the float.”

Source link