Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

How many people would agree that “American-style corporate finance . . . has for the past 40 years been one of the world’s most remarkable success stories” that merits a place alongside “advances in medical and information technology”?

This is the argument Donald H Chew makes in The Making of Modern Corporate Finance, his ambitious attempt to update Adam Smith for the 21st century: “For as Smith suggested nearly 250 years ago, it is the efficiency gains from finding commercial uses for new technologies . . . by mostly private enterprises that end up footing the bill for the health, education, and other forms of general well-being that most of us value most.”

The mercantilist proponents of the tariff war unleashed by President Donald Trump have no truck with Smith. Writing in the FT on April 8 Peter Navarro, the president’s senior counsellor for trade and manufacturing, claimed that cumulative US trade deficits since 1976 “have transferred over $20tn of American wealth into foreign hands” and that the US has lost 6.8mn manufacturing jobs, mostly to China, over that period. He did not mention the benefits America has reaped from an open and competitive system. So there may never have been a more important time to remake Smith’s case.

Chew, the editor of the Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, begins by describing what was wrong with the “old-fashioned corporate finance” of 50 years ago. By the late 1970s, he writes, most large US companies were conglomerates. General Mills, for example, expanded from making breakfast cereals into an “all-weather growth company”, buying manufacturers of toys, Play-Doh, “even small submarines”.

As long as the chief executives who presided over these transformations grew their earnings, they kept their jobs without anyone asking what their cost of capital was, and hence whether their empires were creating value. At one point in the 1970s, the S&P 500 lost almost half its value; by the end of the decade, two professors at Rochester University wrote a paper called “Can the Corporation Survive?”.

On the surface, America continued to struggle in the 1980s as Japan inexorably rose; the Nikkei 225 reached a record 39,000 at the end of 1989 (today the index is around 34,000). In 1992, 25 academics accused US companies of systematically underinvesting compared with their Japanese counterparts. But beneath the surface, something remarkable was happening. The Nikkei fell 60 per cent in the 1990s and did not regain its 1989 peak until February 2024. Over that same period the S&P 500’s total return in the US was more than 3,000 per cent.

Chew traces the ur-moment of this revival of America’s corporate and stock market fortunes, and the invention of “modern corporate finance”, to a classroom at Carnegie-Mellon university in 1957 when Merton Miller (Nobel Prize 1990) taught his first class in corporate finance under the supervision of Franco Modigliani (Nobel Prize 1985).

The aim of M&M, as they became known, was to turn corporate finance from a seat-of-the-pants decision-making process — for example on when and how to borrow money — into “a structured theory and set of practices that would produce a better outcome”. In 1958 they published “The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance and the Theory of Investment”. This foundational text laid the intellectual path for the barbarians who turned up at the gates of America’s conglomerates in the 1980s and proceeded to dismantle them.

What followed were waves of hostile takeovers, share buybacks, replacing equity with debt and taking companies private. The number of US-listed companies peaked at 7,562 in 1998. It is now less than 4,000. Chew reckons that new ways of managing and financing companies contributed to “the rising social wealth of a great many — though by no means all — American citizens”.

Chew is very good at conveying complex ideas in clear language (the first equation does not appear until page 27). But the book’s structure does not help to build his argument. After a compelling introduction there are 10 essays, each based on the work of a leading theoretician. They could be read on a standalone basis, but together they reduce the coherence of the book’s main thesis. Instead of a conclusion that brings everything together, the book peters out with an essay on the benefits of environmental, social and governance (ESG), which already feels dated in the brave new Trumpian world.

The essays provoke two thoughts. First, if the 1970s were the period of old-fashioned corporate finance, and the next 40 years were the period of modern corporate finance, are we now in a period of postmodern corporate finance? A striking thing about the Magnificent Seven — Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla — is how simple they are from a corporate finance point of view. Nvidia, for example, has four times more cash on its balance sheet than debt. The seven have not produced all this value through complex financial engineering.

The second question is: is there anything genuinely new in corporate finance? Major innovations — railways, electrification, the internet, AI — have caused surges in productivity that in turn enabled stock market bubbles. Technology companies were 37 per cent of America’s market capitalisation in early 2025, but railways accounted for 63 per cent of it in 1900. The railway bubble collapsed, but the railways it financed continue to be part of the backbone of the US economy. The Magnificent Seven are now entering into a significant correction — so far this year their market value has fallen by some $2.5tn. But their technologies will continue to change the world.

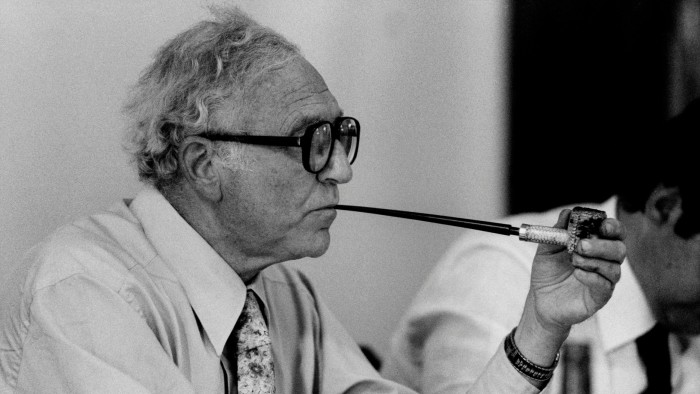

Private equity is one of the main drivers of the period of corporate finance that Chew analyses. It rose as dollar interest rates fell from 20 per cent in 1980 to zero in real terms 40 years later, making a few financiers look like innovative geniuses for replacing equity with cheaper debt. Paul Volcker, chair of the Federal Reserve from 1979 to 1987 and the most consequential central banker during that interest rate cycle, was asked towards the end of his life if he had seen any genuine innovations in finance. He replied that there was only one — “the ATM machine”.

The Making of Modern Corporate Finance: A History of the Ideas and How They Help Build the Wealth of Nations by Donald H Chew Columbia University Press £30/$35, 328 pages

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X