Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Anger is building in South Korea over Chinese fish farming installations in the Yellow Sea, opening another front in Beijing’s tensions with its neighbours over its assertive conduct in disputed maritime territory.

South Korean lawmakers held a rare bipartisan parliamentary hearing last month to condemn steel structures installed by Chinese companies in the Yellow Sea, between China and the Korean peninsula.

Beijing insists the structures are intended for fishing, but officials and experts in South Korea see them as the latest example of China’s “grey zone” tactics, which critics say Beijing uses to bully countries including the Philippines, Vietnam and Taiwan in their territorial waters.

“This is a clandestine tactic to claim our waters inch by inch and restrict the operations of the US-South Korea alliance,” said Jaewoo Choo, head of the China Research Center at the Korea Research Institute for National Security think-tank in Seoul.

Na Kyung-won, a lawmaker from South Korea’s ruling conservative People Power party, accused China of using “gangster tactics” to “block other countries’ access by force” from the South and East China seas.

“A firm and stern response . . . is needed to address China’s unfair attempts to change the status quo,” she wrote on social media.

Beijing has tried to downplay the tensions. The Chinese embassy in Seoul last week defended the steel structures as “reasonable use [of] offshore waters” in line with domestic and international law and did not violate a bilateral fishing agreement between the countries.

China’s foreign ministry spokesperson Mao Ning last month said the situation in the Yellow Sea was “stable” and noted the sides maintained smooth communication through a dialogue mechanism on maritime affairs as well as between their respective maritime law enforcement agencies.

Chinese companies started building large-scale deep-sea fish farms in 2016 for Norwegian companies raising salmon in the Atlantic Ocean.

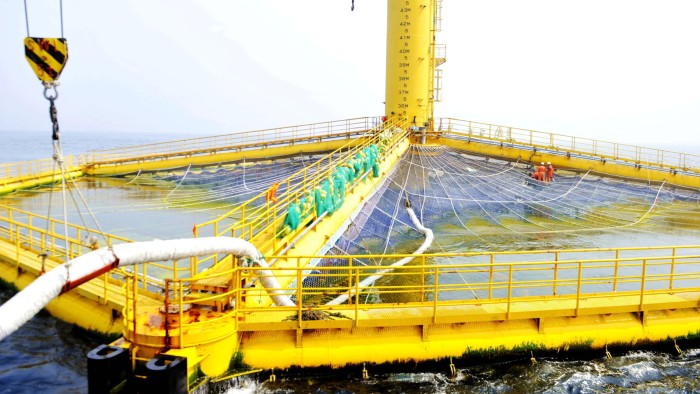

Construction on the first Yellow Sea installation, the Shenlan 1, began in 2018 in the “provisional measures zone”, a disputed area in the Yellow Sea where Chinese and South Korean exclusive economic zones overlap. It was built by Wanzefeng Group, a fisheries company based in eastern Shandong province.

A second structure, the Shenlan 2, was installed last year in the PMZ by a joint venture between Wanzefeng and state-owned Shandong Marine Group, despite Seoul’s protests.

South Korea dispatched a marine research vessel last month to investigate but was forced to turn back after an hours-long stand-off, according to according to South Korean media reports confirmed by the Financial Times.

Neither company responded to requests for comment.

Analysts noted that the structures were consistent with China’s wider policy to “encourage the development of deep-sea aquaculture fisheries” as part of leader Xi Jinping’s drive to promote food self-sufficiency.

But some observers warned that such actions in disputed waters could be a precursor for more solid territorial claims.

“They put their fishing vessels and fish farms there with subsidies and infrastructure support, and after a while they use the fact of that presence to underpin a historic claim,” said a senior government official in the Philippines, which has repeatedly clashed with China in the South China Sea.

That stance has also been endorsed by some Chinese observers. Current affairs blogger Shijiu Chen Nianhuashe wrote last month: “On the surface, we are building ordinary fish farms. But in fact, this is a smart move to increase our actual control in these disputed waters.”

Nam Sung-wook, a professor at the Graduate School of Public Administration at Korea University, said a chain of Chinese structures in the Yellow Sea could ultimately obstruct South Korean or Korea-based US naval vessels from accessing the East China Sea in the event of a conflict in the Taiwan Strait.

“We should have taken action sooner,” Nam said. “If any country doesn’t respond to such territorial issues immediately, it becomes a fait accompli.”

South Korea’s foreign ministry said in a statement that “our justified and legitimate maritime rights in the Yellow Sea should not be violated”, adding that it would “actively respond in the future”.

The tensions come as China is seeking to improve ties with South Korea and Japan, as the US allies reel from Donald Trump’s aggressive trade policies, including a 25 per cent tariff on cars.

The Asian countries held their first trilateral trade meeting in six years last month, where Chinese officials tried unsuccessfully to convince their South Korean and Japanese counterparts to discuss a joint response to Trump’s sweeping “liberation day” tariffs, according to two people familiar with the talks.

South Korea is set to begin trade negotiations with the Trump administration on Thursday. Ahead of the talks, South Korea’s acting president Han Duck-soo told the FT that Seoul would not “fight back” and was open to negotiating non-tariff barriers, citing the country’s historical debts to the US.

Japan also began bilateral trade talks with the Trump administration last week.

Patricia Kim, co-lead of the Global China Project at the Brookings Institution in Washington, said the friction with South Korea in the Yellow Sea was a “textbook example” of how China’s aggressive maritime policies had “alienated many of its neighbours”.

“Even as Beijing seeks to cultivate friendly partners in the region amid growing strategic rivalry with the United States, its assertive actions undercut its diplomatic efforts.”

Additional reporting by Kang Buseong in Seoul and Leo Lewis in Tokyo; cartography by Haohsiang Ko in Hong Kong

Source link