Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

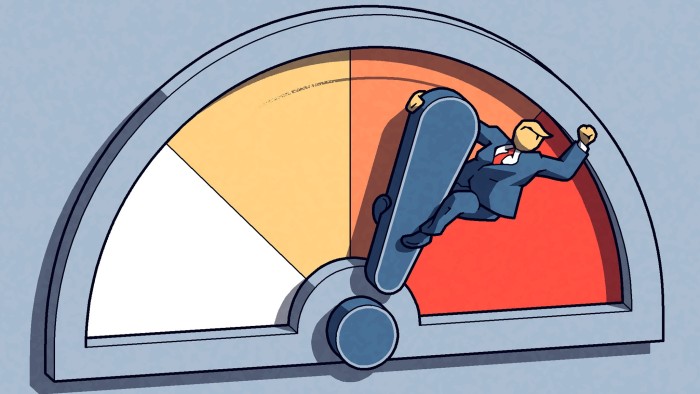

America under Donald Trump is an emerging market. That’s my takeaway from the last few days of tariff chaos and its fallout.

When I first raised this idea last October, I pointed out that emerging markets are often characterised by uncertain economics, corrupt politics, institutions that are too weak to enforce democratic norms, violence and social polarisation. The US has been heading fast in that direction since 2016, for reasons we know all too well, though asset prices and borrowing rates hadn’t yet reflected it.

Instead, we frequently saw US equities and currency rising during periods of political and economic stress between 2016 and 2024, thanks to the haven status of the dollar.

It didn’t seem to matter that all the things that had bolstered American companies, from low rates to financial engineering to globalisation itself, were tapped out. US asset markets seemed impervious to the notion of a dollar-doomsday scenario that would send both currency and asset prices tumbling.

Trump has finally ended America’s exorbitant privilege. The president’s erratic leadership style, which reminds me of the guy who pulls off his steering wheel so that the other driver will be forced to swerve, is now endangering his country’s currency and equity values, as has always been the case in other, non-exceptional political economies with this much turmoil.

As Mark Rosenberg, the founder and co-head of research at the research firm GeoQuant, pointed out last week, “we now see strong, emerging market-level negative correlations between political risk, and both the USD and S&P 500”.

This is not a surprise, though many in the business and investment community have acted as though it should be. Too many CEOs were looking only at the possibility of tax cuts and deregulation in Trump’s second term rather than the broader instability and economic paradigm shift that it heralded.

Trump’s personal behaviour certainly sent plenty of emerging market-like signals. Is there anything more EM than a leader who surrounds himself with lieutenants vetted mainly for absolute loyalty? The more leadership is about cult of personality, the more economic outcomes are determined by the individual ruler, who can give and take with impunity. And the weaker the institutions, the more likely it is that the ruler will get away with it.

Trump’s election was “in many ways a product of the emerging market-like trends in social and institutional stability in the US that we’ve seen growing since 2017”, notes Rosenberg.

Still, it took the threat of economic war on allies and adversaries alike, waged in ways that left even Trump’s own policymakers struggling to keep up, to shift risk perceptions. Poor US trade representative Jamieson Greer was in Congress defending tariffs even as Trump was granting a 90-day reprieve to many countries. Who will take him, or any of Trump’s cabinet, seriously in any future negotiation?

Equity markets, at least until last week, acted as though Trump had some control over the situation he unleashed. When the president posted that it was a “great time to buy” stocks, they rose. That too is EM-like behaviour. I remember back in 2008, when Russia’s then prime minister Vladimir Putin spoke five sentences criticising a coal and steel oligarch, and $6bn was wiped off the company’s value in real time. In Turkey, the lira and other assets move significantly on President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s speeches and pronouncements.

But the bond market knows better, and it has for some time been telling us what equities did not, which is that borrowing rates aren’t going down, and political risk isn’t going away. Even as equities enjoyed the post-election “Trump bump,” yields remained elevated. The fact that bonds, usually a haven, also sold off during last week’s equity market rout tells us that investors were either selling less risky assets to deal with losses elsewhere, or that trust in the US and its future is simply gone.

In fact, last week may be remembered as the true, quantifiable beginning of the end of American economic exceptionalism. “Fear exists all over,” Euronext chief executive Stéphane Boujnah told France Inter radio a few days ago. “The country [United States] is unrecognisable and we are living in a transition period. There is a certain form of mourning, because the United States that we had known for the most part as a dominant nation resembled the values and institutions of Europe and now resembles more an emerging market.”

I suspect that will be true under Trump with or without tariffs. Even if China backs down and humours the president (I don’t think it will), or we end up with only moderate shifts to the global trading system, the damage has been done. Trust is gone. Wall Street and Main Street alike are uneasy, and that changes behaviour.

The capriciousness of Caligula capitalism is going to be with us at least until the midterms (I’m personally planning to be in cash and gold till then). But the legacy will linger much longer, particularly as the Trump tax cuts coming down the pike in a few months create a completely unsustainable debt picture. Is it possible that America could become the epicentre of the next emerging market-style debt crisis? I would have ruled it out once. Not any more.

Source link