“In so far as taste can be changed by one man, it was changed by Roger Fry,” wrote the art critic Kenneth Clark. Fry — prolific art critic and writer, and a painter himself — was a passionate champion of the latest work coming from France in the early 20th century, and determined to convert the English-speaking world to his way of thinking.

He was also a central figure in the circle of thinkers, writers and artists dubbed the Bloomsbury Group (for the London district in which many of them lived), and of whom Dorothy Parker later quipped “they lived in squares, painted in circles and loved in triangles”. One of those triangles — Virginia Woolf’s sister Vanessa Bell, her lover Duncan Grant and his lover David Garnett — moved to a spartan farmhouse between Brighton and Eastbourne during the first world war, because Grant and Garnett, as conscientious objectors, were required to work on the land.

How much of that they did is unclear, but that Sussex farmhouse, called Charleston — richly decorated by Grant and Bell with exuberant paintings on doors, walls and furniture, and hung throughout with works by those artists and their friends — became home to the group’s intellectual heart, regularly visited by Fry, the Woolfs, Vanessa’s husband Clive Bell, and dozens of others. In the outlying barns now expertly converted into galleries, a new exhibition, Inventing Post-Impressionism, helps to explain how Britain finally came to accept the best western art of the early 20th century, and Bloomsbury’s part in that.

The works here — few but very fine — come on loan from the Barber Institute of Fine Arts in Birmingham, a superb art deco building currently closed for an up-do. There, during the 1930s and ’40s, its inspired founding director, Thomas Bodkin, put together one of the outstanding collections of art assembled in Britain in the 20th century.

The show opens with a couple of core impressionist pieces — just to orientate us — including a glorious, tranquil “The Pond at Montfoucault” (1875), sparkling with light, by Camille Pissarro, a central impressionist figure and, appropriately, something of a mentor to younger artists including Cézanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin and Seurat. Next we can see how that new generation — dubbed post-impressionists — wanted to move away into works of more emotional intensity: Van Gogh’s “A Peasant Woman Digging” (1885), made only 10 years after Pissarro’s dreamy bucolic vision, could hardly be more of a contrast in depicting the lot of the rural poor, using sombre, almost threatening earthy colours for its stark portrait of a woman bent double, her face hidden in relentless labour.

In the same room, a snappy portrait by André Derain (later a member of the fauve group), a quasi-traditional landscape by Gauguin and a “Composition with Fruit” by Fernand Léger — already embracing cubism — show the range of styles and techniques that sit under the loose portmanteau of post-impressionism. A small gem is an intimate portrayal of the artist’s mother (1900) by Édouard Vuillard: dressing her hair at a mirror, her face averted, her patterned dress almost blending her into rather fussy domestic surrounds, its then-radical skewed composition shows the influence of Japonisme, the craze for works emerging from Japan at the time.

A very mixed bag, therefore, but each a choice piece, and showing many of the artists that so excited Roger Fry. In November 1910, Fry had organised in London an exhibition entitled Manet and the Post-Impressionists. He’d struggled, according to Charleston’s exhibition, to come up with the term; he apparently said to a colleague: “Oh, let’s just call them post-impressionists. At any rate, they came after the impressionists . . .”

The post-impressionists, therefore, were never a self-conscious grouping. But they were united in seeing their artistic predecessors the impressionists as limited in endlessly seeking to relay the effects of light, water, sky, shadows: theirs was a quest for more interior feeling and more symbolic impact.

Fry’s exhibition was a thunderclap, introducing the British public for the first time to Cézanne, Matisse, Seurat, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Picasso and others. Of course, it was roundly trashed. Fry’s reputation as an art critic took a nosedive and he was branded everything from a subverter of morals to an unscrupulous self-advertiser. Two years later, 1912 saw a second post-impressionist show organised by the undeterred Fry, which included fresh names, including Russians and some avant-garde British artists: Duncan Grant; Fry himself, Eric Gill, Wyndham Lewis. By now, the term Fry had hastily invented was established, and the international reception of these artists too.

There’s a comic element in the show, for light relief: a very funny series of watercolour cartoons by Henry Tonks, made around 1922, entitled “The Conversion of St Roger”. It shows Fry as a messianic evangelist preaching the gospel of the new art. In one frame, he is ludicrously holding up a dead cat and haranguing a bemused audience of fellow artists while the small, pudgy figure of Clive Bell shouts “Cézannah! Cézannah!” (a play on “Hosannah”).

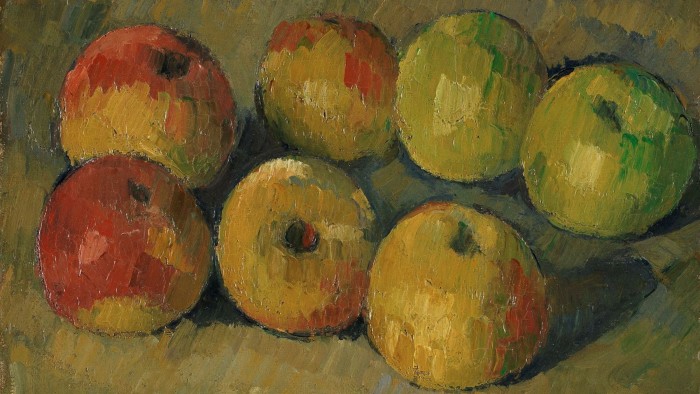

The best is last. The undisputed star of this gorgeous show is a small, glowing still life by Cézanne, no bigger than a laptop screen, a simple depiction of seven apples on a table. It’s something of a homecoming for a Bloomsbury legend, “the Cézanne in the hedge”.

In 1918, Fry told the economist John Maynard Keynes — avid art lover and Bloomsbury insider (he was Duncan Grant’s former lover and lifelong friend) — about a significant sale in Paris of works owned by Edgar Degas. Keynes, who advised the government on art as much else, persuaded the then director of the National Gallery, Sir Charles Holmes, to make the trip across the Channel with him — with a useful £20,000 (about £1.4mn today) of government funds in his pocket.

With the war still raging in France, buyers were few and prices low. Holmes acquired impressive treasures for the National Gallery — by Manet, Delacroix, Corot, Ingres, even Gauguin. Yet, despite Keynes at his side and Fry urging him on from afar, he felt Cézanne was a step too far — so Keynes bought the “Still Life with Apples” (1877-78) for himself, for just £500 (roughly £36,000 today).

But getting it home was a task. The muddy track from the main road up to Charleston farmhouse, where he by then had a bedroom of his own, was impassable to vehicles and Keynes had to walk. Overladen with packages and luggage, he simply stuffed the Cézanne into the hedge on the quiet country road, to be collected later.

Keynes always kept the Cézanne apples over his bed at Charleston where, on a small plain table, gazing out at the tranquil pond, in 1919 he wrote The Economic Consequences of the Peace. On his death in 1946 he bequeathed the picture to King’s College, Cambridge; today it hangs in Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum. Now on loan “back home” at Charleston, it seems more than itself: it tells an eloquent story of how the lives of this group of talented people, centred around a smallish country farmhouse, touched so many aspects of the wider world, in politics, economics, literature, art history and more. This, beyond their individual talents, was probably the Bloomsbury group’s real significance.

To November 2; charleston.org.uk

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning