Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

Donald Trump has followed through on his threats and imposed 25 per cent tariffs on Mexican goods and non-energy products from Canada, 10 per cent tariffs on Canadian energy and a further 10 per cent on Chinese goods.

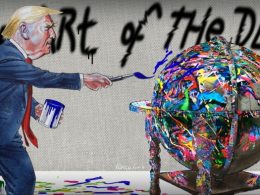

“Tariffs are about making America rich again and making America great again,” the president told Congress on Tuesday evening. “There’ll be a little disturbance, but we’re OK with that. It won’t be much.” Such was his confidence that he promised further levies on imports from Europe, South Korea, Brazil and India from next month.

International macroeconomics is difficult and not obviously grasped by Trump, so here are 10 things you and he should know about his tariffs.

First, they are large. Those on Canada, Mexico and China raise the average tariff on US goods imports from 2.4 per cent in 2024 to around 12 per cent if trade flows remain unchanged. That is therefore an upper estimate, but the result will be US trade barriers not seen since the second world war.

Second, it is important to remember that the importer pays. Tariffs are a tax levied on goods that cross the border.

Third, although the importer pays, the question of who bears the ultimate cost is more complicated. The US supply chain felt the pain for the vast majority of costs following the 2018 tariffs and we should expect something similar today.

Fourth, although the tariffs imposed so far are likely to raise $142bn for the US Treasury, this is less than a tenth of the expected $1,865bn US federal government deficit in 2025 and assumes no behavioural change. Tariffs do not resolve US fiscal incontinence.

Fifth, with goods imports roughly 10 per cent of GDP, increasing the tariff rate by almost 10 percentage points is likely to raise consumer prices by something close to 1 per cent. This rough calculation is similar to more sophisticated estimates, such as those from staff at the Boston Fed this week.

Sixth, a rise in prices is different from inflation, although consumers will balk at my pedantry. There is little doubt, though, that following the great inflation of the past few years, there is a greater risk than pre-pandemic that companies and households will seek to avoid taking a hit when prices rise by demanding compensation through persistently higher prices and wages. That is inflationary.

Seventh, the US is a very closed economy in which total goods trade as a share of GDP was 19 per cent in 2023, compared with 53 per cent in Canada, for example. This is despite Trump’s rhetoric that imports are killing America and explains why US threats are heard louder abroad than at home.

Eighth, the damaging effects of tariffs on the supply capacity of the US economy puts upward pressure on interest rates. The rise in uncertainty stemming from Trump’s actions, by contrast, lowers investment intentions and imparts downward pressure on rates. Investors are becoming more concerned about the latter, but interest rate expectations have still risen since the election.

Ninth, tariffs are far from certain to lower the trade deficit, which exists because the US persistently consumes more than it produces at full employment. The way to guarantee a drop would be to generate a deep recession, cutting demand for imports.

Tenth, tariffs are unlikely to be popular. Raising prices and impeding the purchase of imports by throwing grit into the trading system is rarely a winner with public opinion. Brexit, which did the same, is now wildly unpopular in Britain and Trump understood the public’s hatred of price rises in his election campaign. The public is unlikely to view this as a little disturbance.

One group, however, who will be quietly excited about Trump’s tariff obsession is economists. Explaining wacky policy is great for business and will generate some wonderful data sets to argue over for years to come.

Source link