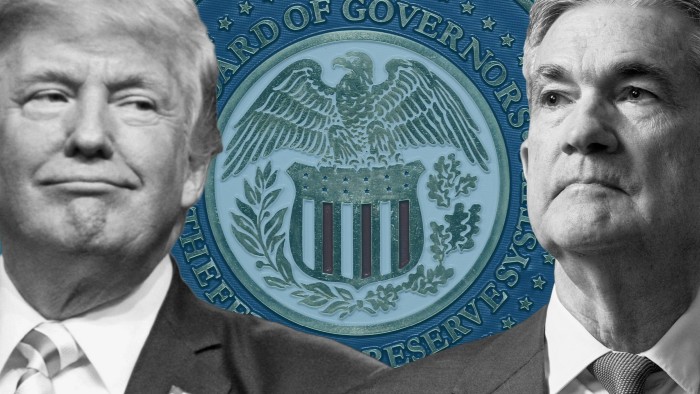

Since Donald Trump’s election victory last year, Federal Reserve officials have pursued a strategy of sticking to their knitting alongside concessions in areas peripheral to the central bank’s core functions.

The Fed has taken down pages from its website on diversity, equality and inclusion, which chair Jay Powell said was “to align our policies with the executive orders”, withdrawn from the international central bank Network for Greening the Financial System and pointedly refused to comment on the merits of tariffs.

Michael Barr, the Fed’s vice-chair for supervision, has announced he will step down from that role to allow the president to make his own pick and last week explained he did not want to become a “distraction” that would “put the Fed in the crosshairs”.

On the big issues, Powell has been adamant that the president could not legally fire him nor members of the Board of Governors and that central bank independence was in the interests of the US economy.

So far Trump has called for the Fed to cut interest rates but not tried to interfere directly. His sidekick, Elon Musk, said last week he wanted to audit the Fed without elaborating. An uneasy calm prevails.

In November I fear I was too sanguine about threats to the Fed, so today, I look at the relevant evidence and ask the question, if Trump wanted to take control, how would Fed independence die? The results are not wholly reassuring.

The personnel putsch

The favoured method of autocrats around the world is to stuff central banks with flunkies who will do their bidding. The standard view is that this will be difficult for the US president. The terms of office for the Fed’s Board of Governors are listed below with only the seats of Adriana Kugler and Jay Powell falling vacant over the next four years.

The Federal Reserve Act states that governors can only be removed by the president “for cause”, meaning they would have to commit serious misconduct in office.

Do not let these facts put you at ease.

On February 12, Sarah Harris, the acting solicitor-general, wrote to Senator Richard Durbin, stating that the Department of Justice no longer believed these “for cause” provisions were constitutional and “the Department will no longer defend their constitutionality”.

She specifically mentioned the Federal Trade Commission, the National Labor Relations Board and members of the Consumer Product Safety Commission, but also included in her argument “a variety of independent agencies” which had “substantial executive power”.

This issue is tangentially already at the Supreme Court regarding the firing of Hampton Dellinger, head of the United States Office of Special Counsel. The justices delayed a decision last Friday. More relevant to the Fed’s position was Trump’s sacking of Gwynne Wilcox, who sat on the National Labor Relations Board. She is also suing.

The Supreme Court has already overturned “for cause” protections for agencies with a single person in charge. Legal scholars suggest there is a good chance a majority exists in the court to overturn this long-standing precedent for multi-member boards of government agencies, giving Trump the power to fire members of the Fed’s board.

In a wonderful paper on the legal position of the Fed, Professor Daniel Tarullo of Harvard Law School, a former member of the Fed’s board, wrote in 2024 that if the Supreme Court were to invalidate for-cause removal protection, “the [Fed’s] Board of Governors would join many other agencies in the crosshairs of ensuing constitutional challenges”.

We do not know if Trump will succeed in court and, if so, whether Fed board members would also be fired, but the personnel putsch is happening in other federal agencies already.

The Regional Fed frailty

A second weakness in the Fed’s constitutional position concerns the Regional Fed presidents who sit on the Federal Open Market Committee.

For their position to be constitutional, Tarullo argues they must ultimately be regarded as “inferior officers” of the US since they have not been appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. This was the view of the Office of Legal Counsel in 2019 although, as Tarullo said, “reaching this conclusion took some doing”.

The problem is that setting interest rates is a more powerful position than most and certainly more powerful than other inferior officers. Voting against a majority of the Fed’s board (say in a 8-4 vote when the majority of the Board of Governors lost the vote, but the five voting regional Fed presidents sided with the minority) would stretch the limits of the constitutional position of inferior officers. The Board could dismiss the inferior officers and push their view through in a special meeting, but, as Tarullo said, scenarios such as these are “no way to run a central bank”.

This issue is not currently live, but things change.

Delegation directive

The most direct challenge to the Fed’s authority would come if Trump decided to challenge its ability to take decisions independently of his view under the authority granted by Congress.

On its website the Fed expresses no doubt that its board “guides the operation of the Federal Reserve System to promote the goals and fulfil the responsibilities given to the Federal Reserve by the Federal Reserve Act”, and that it is “an agency of the federal government that reports to and is directly accountable to Congress”.

But this position is under direct threat from Trump thanks to two executive orders he signed last week, seeking to bring the powers of agencies under his control. The first stated that “officials who wield vast executive power must be supervised and controlled by the people’s elected president”.

The Fed’s regulatory powers were targeted in the order, although there was a carve out for monetary policy. But if this executive order survives inevitable court challenges, that carve out would not be worth much.

This is an area of considerable legal uncertainty. Congress is permitted under a 90-year-old precedent to delegate power as long as it gives an “intelligible principle” for agencies to operate by. A second executive order last Wednesday sought to attack this directly, seeking to abolish “regulations that are based on unlawful delegations of legislative power”.

Tarullo thinks the Fed’s dual mandate is potentially vulnerable here because the dual mandate of stable prices and maximum employment can be in conflict and is therefore not an intelligible principle. The application of the Supreme Court’s recent thinking here, he wrote, “suggest[s] significant, if not major, problems for the Federal Reserve Act”.

Since Tarullo wrote his view last year, I caught up with him yesterday to get his view on where the manoeuvres of the past few days have left the Fed.

Professor Tarullo said there was little doubt these issues would be litigated and the case to watch was that of Wilcox, who was fired from the NLRB. If her for cause protection was deemed unconstitutional, “every independent agency is called into question”. The Fed might have some special arguments why it was different or the NLRB case might be tightly defined, he said (outlined in his paper), but a direct finding by the Supreme Court would raise questions about the constitutionality of the Fed’s board.

That said, Tarullo saw little desire yet from the new administration to attack the Fed. “It is in the administration’s own interest not to suggest it will displace Jay Powell or other governors. It looks as though they understand that,” he said. But efforts to separate monetary policy from financial regulation in the Fed’s toolkit contain many grey areas such as the Fed’s lending arrangements to banks and macroprudential policy, which complicate the carve out in the first Trump executive order.

It might just be down to financial market reaction if Trump decided to strike.

FAIT’s fate

Talking of things being lined up ready for the chop, the Federal Open Market Committee gave notice that days were numbered for flexible average inflation targeting (FAIT).

FAIT was introduced into the Fed’s statement on longer-run goals and monetary policy strategy after a 2019-20 review and stated that the Fed would seek to run inflation moderately hot for a time “following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 per cent”.

In the minutes, officials noted that the economy had changed a lot since 2020 and it wanted to review elements introduced then. The most significant likely change highlighted was “the approach of aiming to achieve inflation moderately above 2 per cent following periods of persistently below-target inflation”.

FAIT’s fate is sealed.

What I’ve been reading and watching

-

Losses mount up at the ECB as the interest it pays on bank reserves (to set the overnight interest rate) are higher than the yield of the bonds bought under the quantitative easing programme. Because the losses are not immediately recognised and offset with new capital unlike in the UK, the ECB will not be paying dividends to its member states for some time to come

-

Also in Frankfurt Isabel Schnabel, a member of the ECB’s executive board, gave a hawkish interview to the FT. Full transcript

-

When will the US bond market revolt against fiscal largesse? Is it financeable? “It is, until it isn’t,” Mark Sobel, former US Treasury official, tells the FT in a big read well worth your time

-

And if you like charts, check out the visual feast on the first month of Donald Trump’s second presidency

A chart that matters

Corporate earnings calls are a great alternative source of rapid information highlighting the concerns of companies. In recent weeks, the number of sentences linking trade with corporate risk have shot up in the US (chart below) and also in other countries, especially Mexico and Canada.

Business investment caution in the face of trade uncertainty is one big downside risk to the global economy this year. We shall see soon enough whether executive concerns are translating into lower spending.

Source link