Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Well, is it the Gulf of America or the Gulf of Mexico? Is it Mount McKinley or Mount Denali? For Google Maps users, the answer will depend on whether you live in Donald Trump’s America or the rest of the world.

In complying with Trump’s insistence on renaming the gulf and America’s highest mountain, Google said this week it had “a longstanding practice of applying name changes when they have been updated in official government sources”.

Users of the app outside America will continue to see existing names, but this is unlikely to satisfy Mexican president Claudia Sheinbaum. Before Trump’s inauguration, she took a swipe at his plans to retitle the gulf. Vast tracts of the US that once formed part of the Spanish empire and later Mexico might be renamed “América Mexicana”, she suggested.

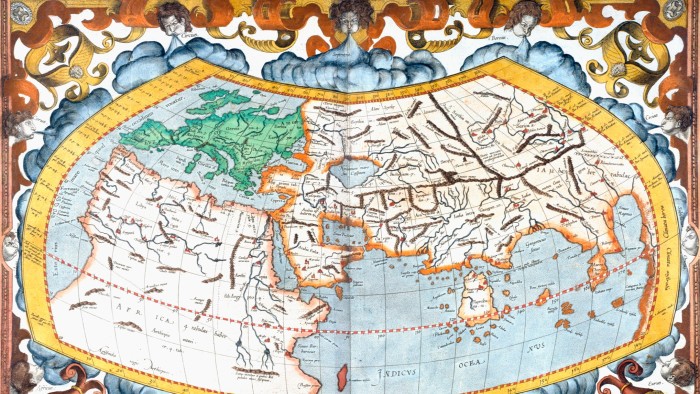

Google isn’t the first and will assuredly not be the last mapmaker to fall in line with a government’s wishes. Down the centuries, maps have served ideological, imperialistic, religious and cultural purposes more often than impartial scholarship — as Mark Monmonier, a US geographer, sets out in his book, How to Lie with Maps.

Great powers have a penchant for maps that express territorial claims or national grandeur. In recent years, China has held a “national mapping awareness publicity week”, encouraging citizens to think of Taiwan and parts of the maritime zones of nearby Asian countries as Chinese.

In Vladimir Putin’s Russia, the government has used anti-extremism laws to clamp down on maps that question whether Crimea, annexed from Ukraine in 2014, or the Kuril Islands, seized from Japan in 1945, belong to Russia.

Smaller countries are just as likely to get in on the act. Since the former Yugoslav republic of Macedonia gained independence in 1991, a long-running sore in relations with Greece and Bulgaria has been the use of nationalist maps that include parts of both countries as “Greater Macedonia”.

Viktor Orbán, Hungary’s prime minister, promotes maps that show his country with pre-first world war borders, including areas of modern Croatia, Romania, Serbia and Slovakia. Ludovic Orban, Romania’s former premier, once brushed these efforts off with a Romanian proverb — “the sparrow dreams of the dough” — implying Hungary’s leader was indulging in fantasy.

During the cold war, even weather forecasts contained political messages. West Germany’s ARD network displayed Germany with pre-second world war frontiers, challenging the communist East German state’s legitimacy.

Before our times, physical maps published with explanatory texts often betrayed their creators’ assumptions. An 18th-century Japanese map of the world observed of Brazil: “The inhabitants of this country do not build houses . . . They like to eat human flesh; however, they only eat men and not women. Their clothes are made from birds’ feathers.”

In western countries, our mental picture of the globe remains profoundly influenced by a 1569 map produced by Gerardus Mercator, a Flemish cartographer. In his effort to depict the three-dimensional Earth on a two-dimensional map, Mercator made places far from the equator look relatively larger. This is why Greenland appears about the same size as Africa, though it is not even a tenth as big.

Come to think of it, could Denmark avoid ceding Greenland to the US, as Trump wants, by using maps to flatter his ego? A US-friendly government in Warsaw once proposed naming a Polish military base after the president. That brainwave came to nothing — meaning the name is free for use. Perhaps Greenland’s capital, Nuuk, known until 1979 as Godthåb, could be renamed Fort Trump.

Source link