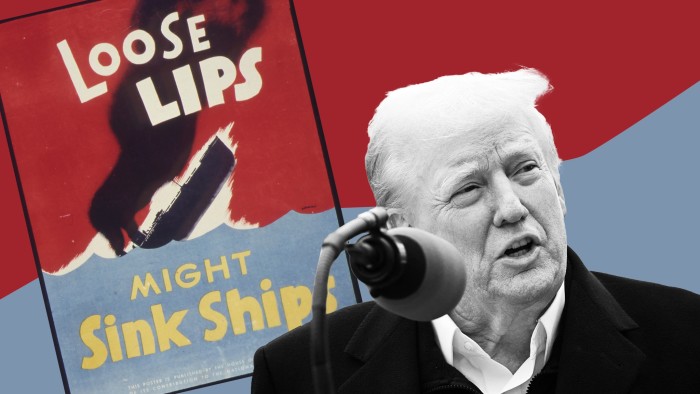

The US phrase “loose lips sink ships” has its origins in second world war cautionary advertising. The UK version, “careless talk costs lives”, also highlighted the importance of precise language and the potential pitfalls in gossip, riffing on a subject or the British professional class penchant for winging it. In his first week back as president, Donald Trump has certainly had loose lips when it has come to economic policy.

In these circumstances, any sentient human must feel for news reporters. They have had to report that Trump was shying away from tariffs, linking tariffs to oil deals, linking tariffs to a TikTok deal, threatening large tariffs on Canada and Mexico within days, softening his stance on Chinese tariffs and imposing then pausing tariffs on Colombia. Those were just some of the stories last week, all accurately reporting Trump’s views when he opened his mouth.

There was similar careless talk from the new president on global taxation (No, Mr President, value added taxes do not discriminate against US exports), foreign direct investment and oil prices. But so far, financial markets have been admirably grown up about all this rhetoric. Trump has barely made a difference.

When speaking to the main hall at the World Economic Forum in Davos, he told Saudi Arabia “you gotta bring down the oil price”, and he expected more than the promise of $600bn of foreign direct investment from the country. I have no objection to a bit of bullying when it comes to an oil-price cartel. But did it work? Did his words and veiled threats have any meaningful effect on the oil price? No.

Oil prices fell a little. But the move was small even in comparison with oil price movements this year and has since reversed. Saudi Arabia’s economy minister Faisal Alibrahim did what any good cartelist does in these circumstances and denied that Opec+ was trying to keep oil prices high. “The kingdom’s position, Opec’s position, is all about long-term market stability to make sure that there’s enough supply for the growing demand,” he said in Davos.

Trump’s thinking about the economic effects of lower oil prices was reasonable, except for the unnecessary bluster. “With oil prices going down, I’ll demand that interest rates drop immediately,” he said. “And likewise, they should be dropping all over the world.”

Did this talk impress forward interest rate markets? No. Over the week, US interest rate expectations for the end of 2025 barely moved, putting no additional pressure on the Federal Reserve. The effect on Monday of Chinese AI start-up DeepSeek on lowering forecasts for energy demand was much more powerful.

With financial markets taking a welcome and adult view of Trump’s threats, I will say one other thing, which will be blindingly obvious to macro economists. The president’s economic reasoning is generally incoherent.

If he achieves much higher capital inflows from Saudi Arabia and companies around the world investing in the US, that has to be balanced by a larger current account (trade) deficit. Olivier Blanchard, former chief economist of the IMF, made the point on X.

If your tariffs reduce imports and increase domestic production (a big if), this will largely be offset by higher inflation because you hit real resource constraints.

Anyway, I will not make a parsing of Trump’s words a regular feature here because the conclusion from the first week of his return is different from the second world war advert.

Loose lips rewrite few scripts.

Stalling scanners

Last May, I wrote about the spread of scanner data to improve inflation measures, especially in groceries. This allows statistical agencies to have sight of both prices and quantities in real time and should bring about more accurate inflation figures. Australia is the world leader here.

I confidently asserted that the UK was going to introduce scanner data for food and non-alcoholic drinks from March 2025 and would publish early estimates of the likely effects by the end of 2024.

Apologies. At the time I fell for the spin from the UK’s Office for National Statistics that it would stick to its timetable. I was wrong. In a strange blog post last week, the ONS came clean that when it said March 2025, it really meant March 2026. In the blog, it promised to explain the delay but that seemed to slip the author’s mind apart from reassuring us that it was a prudent decision.

I understand that staffing shortages are at play, with some concerns that the results might not be sufficiently robust yet. In any case, the ONS did publish the differences in price inflation using the old and new methods for four items: cheddar cheese, milk, berries and olive oil.

As the chart shows, these can be large, but do not always go in the same direction. It is not exactly the impact assessment promised because there is no explanation of why the categories were picked. I’ve shown the results for cheddar cheese, where the inflation rate was twice almost 10 percentage points lower using scanner data, but click on the chart to see the other items.

It’s all rather disappointing. Again.

Bond blues

January 2025 has been exciting in government bond markets. US 10-year yields rose almost 0.3 percentage points (30 basis points) in the first half of the month, triggering concerns about the nation’s budgetary sustainability. Most major European yields matched the moves.

In the second half of the month, yields reversed, sending government borrowing costs back close to the levels they started the year. Think of the hundreds of thousands of words written on a rising term premium; or the suggestions that the US, UK or France had a specific problem identified by the smart people in bond markets. All this effort is now wasted.

More important, what it shows is the need to avoid data dependence on market moves until they have a certain, but difficult to specify, duration. You would be nuts to condition your economic policy or even your forecasts on something this volatile, but it is what the European Central Bank and Bank of England do. It would be even madder to constantly update your fiscal policy on the basis of such moves, as the UK does.

Such data dependence produces the opposite of the monetary and fiscal stability we desire.

What I’ve been reading and watching

A chart that matters — tenacity in Tokyo

The Bank of Japan last week raised its interest rate to 0.5 per cent, brimming with confidence and saying that it was now basing its forecasts and policy on “a virtuous cycle between wages and prices continuing to intensify”.

The chart shows core inflation in Japan and the FT core measure which combines many alternative measures of underlying inflation in a statistically optimal way. Read more about it on the FT’s Monetary Policy Radar. Click on the chart to see the measures at different time periods.

I also have a survey for readers. How confident are you that Japan has now resolved its long deflationary biases? Is it looking good or another false dawn? Click here to vote.

I’ll bring you the answers next week.

Source link