A tale as old as time and yet insistently of the present. A young woman — as far away as India — feels the pull of Lady Liberty’s lifted torch in New York Harbour and crosses the globe to make a new life. She knows her path won’t be straightforward — but also that the Big Apple is the place to support and nurture her dreams.

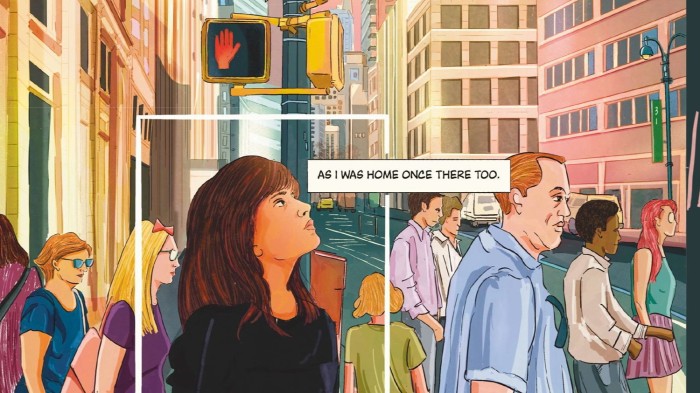

Kay Sohini’s graphic memoir This Beautiful, Ridiculous City, is a praise-song to her adopted home. Raised in the suburbs of Kolkata and given an English education, the young Sohini read Jack Kerouac, Joan Didion and Alison Bechdel and dreamt always of New York. When she finally moved to the city, leaving behind an abusive relationship, she felt she already belonged. At the same time however, Sohini refuses to look away from the city’s flaws, from the damage its ruthless metamorphoses can inflict.

In the days before the inauguration of the 47th President of the United States some of the hundreds of thousands of migrants who have made their way to the city — which has a legal obligation to provide shelter to anyone who asks — have begun to flee, fearing Donald Trump’s threatened deportations. The city, undoubtedly, has creaked under the weight of open-palmed welcome; Mayor Eric Adams’ chaotic administration (with the mayor himself under federal indictment and with many of his top officials having resigned amid a torrent of investigations) hasn’t helped matters.

Yet the city that never sleeps has survived plenty worse, and Sohini’s book, with its glorious, candy-coloured drawings of the Empire State Building, Grand Central Station and the Gimbels Skybridge, presents its allure in a fresh, enchanting way, while also offering a reminder that Sohini is one of a long line of women who have found themselves in the city, made their mark, remade themselves. She loves New York for “the stories it is home to, the creativity it lends to passers-by when the mind is desolate. It is about drawing pleasure from proximity. To possibilities, to art, architecture, culture, history, luxury.”

In this she is not so far removed from the writer and raconteur Fran Lebowitz — the professional New Yorker whose fame increased exponentially with the release of Martin Scorsese’s 2021 documentary Pretend It’s a City. As she has it in her author biography: “Lebowitz lives in New York City, as she does not believe she would be allowed to live anywhere else.” Lebowitz is of course herself an immigrant to New York, albeit one from just across the river in New Jersey. But to New Yorkers, that’s far enough.

The struggle to be a New Yorker is real. Although Sohini is captivated by Manhattan, she finds a place to live in Queens, a fair few subway stops from the landmarks she draws with such care and affection. This moving, optimistic book doesn’t shrink from economic reality, as she watches local residents being displaced from her neighbourhood as the outer boroughs gentrify too.

“With the median house price hovering around $700,000, homeownership is a pipedream to many. Nearly 70% of the city’s eight and a quarter million people are renters.” She draws the facade of a red-brick apartment building, beautifully restored and for that very reason forbidding: “New York is increasingly a city for the very moneyed,” reads the text that runs across the brick. “It makes less and less space for those with little or modest means.”

Not long ago, the city seemed — just — somewhat more accommodating to those who would see in Lady Liberty not just as a beacon but a mirror too. I read Sohini’s memoir alongside Vivian Gornick’s striking memoir, The Odd Woman and the City — first published in the US a decade ago, but only now appearing in Britain — and Elaine Kraf’s eccentric, compelling novel The Princess of 72nd Street. Put all these alongside Virago’s new edition of The Fran Lebowitz Reader and you have a shelf of works that offer a multi-faceted portrait of what it means to be a woman in New York.

Gornick, long a writer for the storied Village Voice and the author of Fierce Attachments (lauded as the best memoir of the past 50 years by the New York Times Book Review) takes her title from George Gissing’s 1893 novel The Odd Women — a proto-feminist text, if you like, considering as it does the costs of “respectability” for women’s lives. Gornick sets her sights on the three elements defining her existence: her reach for friendship, her desire for romantic love and, most powerful of all, the rhythms of the city she calls home.

She is “a walker in the city”, one of those who feeds “the never-ending stream of the never-ending crowd that is certainly imprinting on someone’s creativity”. Gornick treks the length of the island with her friend Leonard; along the way she records her encounters and recalls her failed love affairs.

The streets and avenues sustain her, the risks and possibilities of the place never permitting the finality of despair. At the end of this brief, peculiarly arresting book she sits down to a solitary dinner and recalls all the New Yorkers who have crossed her path that day. “I hear their voices, I see their gestures, I start filling in lives for them. Soon they are company, great company.” In New York, phantom companionship is companionship all the same.

Gornick quotes a letter by the poet and critic Louise Bogan that describes the West 70s in Manhattan as “that area which absorbs the queer, the old, the failures, into furnished or hotel rooms, and adds gloom to their decay”. Like so much of Manhattan, this part of the Upper West Side has been ruthlessly gentrified; there’s very little room for failures there these days. That raffish neighbourhood was at the tail-end of its existence in 1979, when Elaine Kraf’s cult classic The Princess of 72nd Street first appeared.

Kraf was a writer and painter; the author of four published works of fiction, as well as much work that never made it into the public sphere, she died in 2013. The Princess of 72nd Street is narrated by Ellen, an artist gifted with episodes she calls “radiances”. “I am glad I have the radiance,” the novel begins.

It is these radiances that enable her to become Esmerelda, the Princess of 72nd Street, glorious in a long skirt, patterned with “cascades of color”, a great amulet hung from her neck — sometimes a cross, sometimes a Star of David, sometimes an Egyptian ankh — and her “glittering eyes” painted Cleopatra-style.

Ellen/Esmerelda fights to preserve her independence against the tides of control: the men who want to sleep with her, the doctors who want to medicate her. Her radiances are perhaps bipolar episodes, if we’re going to try clinical language: but this slender novel immerses us in the brilliance of its world so we feel as far from madness as its protagonist does.

Comparisons have been made to the work of Jean Rhys; I thought too of Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar and Leonora Carrington’s The Hearing Trumpet. In the Princess’s consciousness, the ecosystem of the Upper West Side depends on her magnanimous rule: “If I should move away it would fall apart.” She describes with loving care its tattered, accessible charm. “Tomatoes and radishes grow in boxes placed on dirty windowsills. A tan can be gotten free in Riverside Park, and there are always places open for late night wanderers.”

The women in these books seem irrefutably modern: yet this is a modernity that New York has long offered, even in an unlikely way. For there sits Catherine Sloper, settled on “the chaste upholstery of a New York drawing-room” in Henry James’s brief, intimate novel Washington Square, first published in 1880. In those days, her widower father’s grand mansion was “up town”, away from the hustle and bustle of lower Manhattan. The same year the book came out, construction began on an apartment building so far uptown it was seen to be in a veritable wilderness — and nicknamed the Dakota as a result.

In Washington Square poor Catherine is pitied by Dr Sloper, mired in grief after the loss of his wife; she appears at first to be the victim of her father’s disregard and her aunt’s romantic machinations. Catherine’s Washington Square mansion might seem to be a prison; certainly, she is trapped by the morals and mores of her time. But the novel’s end finds Catherine serene in her solitude, a mistress of the city in her own quiet way.

New York’s constant reinvention should make it feel precarious; instead, it delivers a unique sense of permanence, allowing those who find a foothold — not least women on their own — to discover a sense of permission unavailable elsewhere. This beautiful, ridiculous city, indeed.

Each of these books demonstrates that no matter the cost of living, no matter how broken the subway or how much garbage is piled in the street, New York still exerts its glorious pull — somehow makes room for those who would hear its siren jazz. A hell of a town, just like the song says.

This Beautiful, Ridiculous City: A Graphic Memoir by Kay Sohini Jonathan Cape £20, 128 pages

The Odd Woman and the City: A Memoir by Vivian Gornick Daunt Books £10.99, 184 pages

The Princess of 72nd Street by Elaine Kraf Penguin Modern Classics £9.99, 160 pages

The Fran Lebowitz Reader by Fran Lebowitz Virago £10.99, 336 pages

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X