Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

Donald Trump was widely expected to launch a tariff war as soon as he returned to office. In the event, the first shots in his war on the globalised economy happened on quite a different front. In his flurry of orders and memos this week, Trump definitively withdrew already shaky US support for the global compromise on taxing the profits of multinational corporations, a reform painstakingly worked out over the past decade. He also threatened punitive retaliation on any country levying “extraterritorial” or “discriminatory” taxes on US multinationals.

The new administration’s challenge to the global deal is bad news all round. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, it was clear to cash-strapped governments and their taxpayers that the old web of bilateral treaties designed to avoid double taxation increasingly facilitated double non-taxation for multinational companies. The ability to avoid tax by allocating profits in low-tax jurisdictions was not politically or financially sustainable.

This problem affected the US, too. Domestic rules making it easy to park accounting profits in tax havens reduced the US tax take and discouraged companies from investing or redistributing their funds at home. That is why, ironically, the first Trump administration helped drive reform forward. Much early political lifting was done by the then Treasury secretary Steven Mnuchin and his French counterpart.

Agreement on profit-sharing and a minimum corporate tax rate was reached in 2021, but failed to be passed by Congress under the Biden administration. Some of the reforms are already being implemented in many countries, however, potentially boosting global tax revenues by roughly $200bn.

The US interest in reform had been prompted by other countries rebelling against the presence of large US businesses — in particular tech companies — that paid vanishingly little in tax. The UK, France, Italy and others passed laws to levy digital services taxes on such companies’ local revenues. Turnover taxes are typically not covered by tax treaties, and they incurred Washington’s ire. When the international tax deal was struck, these countries offered not to levy their DSTs in order to facilitate a multilateral approach.

US withdrawal from the reform will first of all hurt America itself. Other countries may continue to apply the global minimum tax rule against US companies or decide to reactivate their DSTs, unless Trump somehow bullies them into submission. If he manages to torpedo the rules’ adoption by the rest of the world as well, we would return to the under-taxation of the past, with the same incentives for US and other multinationals to salt away profits offshore.

A better outcome is conceivable. The EU has said it aims to hold discussions with the new administration on how to achieve the goal of ensuring effective minimum taxation of multinationals. Even if a change of heart seems unlikely in the White House, other countries should strive to tax multinationals’ profits sensibly within a coalition of the willing. They have a number of options to deal with the US and other non-collaborating nations. Countries with DSTs could simply let the levy work; those without could introduce one. A co-ordinated approach at the EU level could be pursued, although that would not be straightforward. The repercussions if the Trump administration retaliated, meanwhile, could be grave.

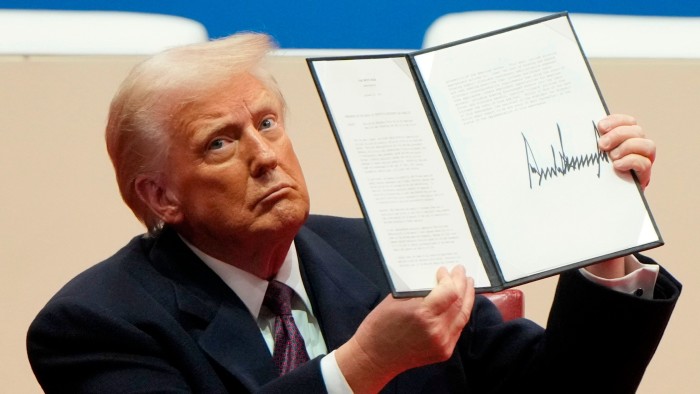

Trump has threatened both tariffs and punitive US taxes on citizens and companies from countries that defy his demand. Those countries are not powerless to push back. But the stakes are high. With a stroke of a pen, Trump has raised the risk that a whole web of cross-border investment stakes might be unwound.

Source link