Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is Norway’s minister of finance

Governments worldwide are thinking about how to best design tax systems to ensure that their economies can stay competitive and become environmentally sustainable, while continuing to raise sufficient revenues.

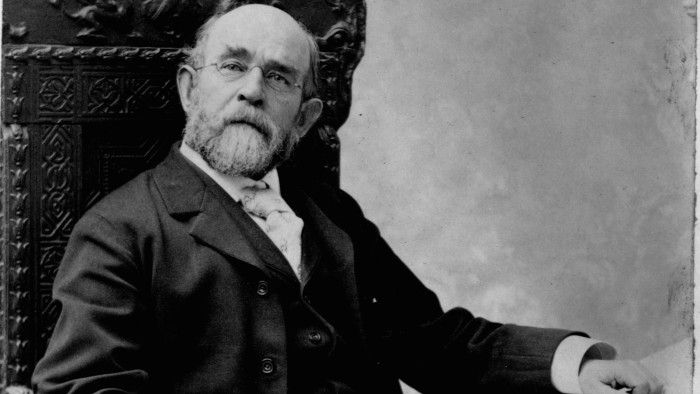

In this context, it is worth revisiting the ideas of Henry George, the 19th-century American political economist. His views on how economic progress can lead to extraordinary revenues for some in society, due to their privileged access to land or other common resources, throw valuable light on today’s tax debate.

In the late 19th century, when the railways were expanding westward in the US, George pointed to the extraordinary increase in the value of land resulting from where the tracks were being laid. He argued that this should benefit everyone, not just those who happened to own the land.

As a politician, George campaigned for the replacement of all other taxes with a single tax on land rent. Unfortunately, we will never know what would have happened had he succeeded: while campaigning to be the mayor of New York in 1897 he died from a stroke. But his ideas travelled across the Atlantic to Europe.

Ever since Norway became an independent nation at the start of the 20th century, the political consensus has been that “super” profits from harnessing natural resources should benefit the whole nation. This principle was first applied to the regulation of hydropower production. Later, when oil was discovered in the North Sea, Norwegian energy policy sought to ensure that a substantial portion of the profits from petroleum production would accrue to society in its entirety. In recent years, the government has taken this principle further, introducing resource rent tax on aquaculture and onshore wind power.

George’s thinking also offers an interesting starting point when considering how to tax super-profits globally. In his railway analysis, the issue was how to fairly redistribute the value of specific chunks of land. In the global economy on the other hand, super-profits can arise when enterprises are not located in a single place.

Such companies often make use of comprehensive user data from social media or other digital platforms, or intangible assets such as international patents. They also benefit from specialised global value chains. The results are significant synergies, considerable market power and profits on a hitherto unimaginable scale.

In a globalised and digitised world, we will need to go beyond George’s ideas. If highly profitable international enterprises that operate across borders are to pay taxes where the revenues are generated, international tax co-operation is key. Currently, several commendable multilateral initiatives are under way to solve these challenges.

It is also clear that George’s single tax or other traditional approaches will not solve today’s challenge of taxing super-profits generated by large multinational companies with mobile assets operating in technology or pharmaceuticals. However, I believe most people would agree that some of these super-profits should benefit the states that offer the necessary infrastructure to allow these enterprises to create value in the first place.

The only way to achieve this is through international tax co-operation. The OECD and G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting has already laid the foundations for fairer and more efficient taxation of multinationals. A global minimum tax of 15 per cent is implemented in more than 50 jurisdictions and counting. “Pillar one” of the framework has the potential to address many of the challenges we face in taxing these companies.

Were he alive today, George would remind us that governments should ensure that super-profits benefit their citizens. International tax co-operation is the way to do this.

Source link